#113: How Do Thunderstorms Form? – Nature's Archive

Summary

Have you ever wondered why some rainshowers turn into thunderstorms? Just what happens in the atmosphere to create these dynamic, exciting, and sometimes damaging storms?

I find it fascinating, because so many interesting principles are at play – things we often overlook. Like, did you know that the sun doesn’t actually directly warm the air? Yes, you heard that right.

Today we take a look at how thunderstorms develop, how they can turn tornadic, and of course, I tie this back to ecology. We discuss the three ingredients needed for thunderstorms – moisture, lift, and instability – and how sometimes even that is not enough. And then there is the fourth ingredient needed to create tornadic thunderstorms.

You may know that I’ve been a weather nut since I was a kid. Back in grade school, I was so obsessed with tornadoes that I decided I’d write a book about them. My mom would take me to the library so I could check out every weather book I could find. Then I’d head home, pull out my dad’s old typewriter, and create my own newsletter — Weather Extra. My subscriber list? Just me. But I was hooked.

So I hope you enjoy this topic, a bit different than our typical episodes!

Did you have a question that I didn’t ask? Let me know at podcast@jumpstartnature.com, and I’ll try to get an answer!

And did you know Nature’s Archive has a monthly newsletter? I share the latest news from the world of Nature’s Archive, as well as pointers to new naturalist finds that have crossed my radar, like podcasts, books, websites, and more. No spam, and you can unsubscribe at any time.

While you are welcome to listen to my show using the above link, you can help me grow my reach by listening through one of the podcast services (Apple, Spotify, Overcast, etc). And while you’re there, will you please consider subscribing?

Links To Topics Discussed

Example Forecast Discussion available on your National Weather Service website.

Soil Moisture and Convection: https://journals.ametsoc.org/view/journals/apme/49/4/2009jamc2146.1.xml

Credits

The following music was used for this media project:

Music: Spellbound by Brian Holtz Music

License (CC BY 4.0): https://filmmusic.io/standard-license

Artist website: https://brianholtzmusic.com

Transcript (click to view)

Michael Hawk owns copyright in and to all content in transcripts.

You are welcome to share the below transcript (up to 500 words but not more) in media articles (e.g., The New York Times, LA Times, The Guardian), on your personal website, in a non-commercial article or blog post (e.g., Medium), and/or on a personal social media account for non-commercial purposes, provided that you include attribution to “Nature’s Archive Podcast” and link back to the naturesarchive.com URL.

Transcript creation is automated and subject to errors. No warranty of accuracy is implied or provided.

[00:00:00] Michael Hawk: Spring has arrived in the northern Hemisphere, and for those of us in North America, that means the skies are about to get loud. Thunderstorm season is here. In fact, there have already been several outbreaks of severe thunderstorms and even tornadoes.

[00:00:13] If you’ve listened to this podcast for a while, you may know that I’ve been a weather nut since I was a kid back in grade school. I was so obsessed with tornadoes that I decided I was going to write a book about them. My mom would take me to the library so I could check out every weather book I could find.

[00:00:26] Then I’d head home, pull out my dad’s old typewriter and create my own newsletter called Weather Extra. My subscriber list. Well, it was just me, but I was hooked.

[00:00:36] Of course, thunderstorms can be exciting, but what I really love about them is how understanding just a little bit about thunderstorms helps us understand several fundamental features of our atmosphere and weather in general. So I’ve put this episode together with the hopes that it gives you a newfound appreciation for weather and our atmosphere.

[00:00:54] And of course, I’ll throw in a few ecological connections as well. Before I get into the episode, I wanted to pass along an amazing update. I’m recording this at the start of April, 2025. For you time travelers who are listening in the future.

[00:01:07] But the update at this time, jumpstart Nature, is now officially a 5 0 1 C3 nonprofit organization. In fact, that designation is retroactive back to April 16th, 2024. If you’re one of our kind donors or Patreon subscribers, this means that your donation might be tax deductible. I say might be simply because everyone’s tax situation is different.

[00:01:28] So consult an expert if you’re unsure. More importantly, this unlocks a bunch of important next steps for us. In addition to adding another layer of legitimacy in the short term, it does mean some extra work, but I consider it foundation building, so I’m looking forward to it. Okay, onto our episode. How do thunderstorms form?

[00:01:48] You may have heard your TV meteorologist say that thunderstorms need three ingredients, moisture, instability, and lift. So where to start? How about moisture? The air in our atmosphere can hold an incredible amount of moisture in the form of water vapor. We measure this in various ways, but perhaps the most common way shared in public weather reports is relative humidity.

[00:02:11] You know, maybe you have 80% humidity in New Orleans in the summer, or 10% humidity in Phoenix in June.

[00:02:19] But I do have a mini rant about relative humidity and how it’s characterized and understood. My issue is that the relative part of relative humidity is rarely explained relative to what? Well, as the air temperature warms, more water vapor can be held in it.

[00:02:36] So when you hear 80% or 10%, that’s the percent of water capacity relative to the current temperature. So that’s where relative comes from. On a typical day, you’ll notice that humidity readings in the morning are much higher than in the afternoon after it warms up. Just yesterday at my house as an example, I had a humidity reading of 93% in the morning.

[00:02:58] Sounds pretty sticky, right? Well, by afternoon it had dropped to 35%. In fact, it was a pretty dry day. The amount of moisture in the atmosphere didn’t change, but the temperature did, and that’s why the humidity percentage seemed to drop. Now there are better ways to assess humidity. A good way to think about it is what happens if you hit 100% relative humidity?

[00:03:21] That means the air is saturated, right? From what I described a moment ago. You know, that means that you’ve hit the point where the air at that temperature can’t hold any additional moisture. This is known as the dew point, the point where water condenses into droplets. The dew point is a good measure for the amount of moisture in the air at the point it’s being measured anyway.

[00:03:43] My rule of thumb is that a 60 degree Fahrenheit dew point is where you start to transition from dry to uncomfortable. 70 degree dew points begins to be very humid. If you’re wondering, record dew points range from the upper eighties to around 90 degrees in the United States, and you might be surprised to learn that Minnesota and Wisconsin are home to some of these top dew points.

[00:04:06] Alongside the typical suspects like Florida and Louisiana, of course, humidity and Dew Point are measured in a specific location, and most of the readings you and I consume are taken near the surface, typically around six feet above the ground. But the atmosphere is three dimensional and very dynamic. So keep in mind that temperatures and moisture content might vary dramatically as you go upwards.

[00:04:31] We’ll talk more about that later.

[00:04:32] Now this moisture that we’re talking about, where is it coming from? Generally, it’s evaporation from the oceans or other bodies of water. There can be small amounts added from ground evaporation as well, and evapotranspiration from plants, especially dense high water content plants.

[00:04:49] In fact, there have been some recent studies showing how miles of highly irrigated crop lands in the Midwest. Impact humidity and storm development. And I’ll link to that in the show notes if you’re interested.

[00:05:00] Even if you’re far away from large bodies of water, large high pressure and low pressure systems, can pull moisture laden air, hundreds of miles. So that’s our first ingredient, moisture. Briefly explained. Now let’s explore the second essential ingredient for thunderstorms lift. Okay. In order to understand why lift is an ingredient, we have to first understand atmospheric heating.

[00:05:24] I think we all know that mountaintops are cold, but why is that? Well, it all starts with sunlight. Imagine a crisp, cool morning, the sun rises and it starts to warm up. No surprises here. I think we all know the sun warms the earth, but what you may not know is that sunlight does not really warm the air itself in any meaningful way.

[00:05:45] Let me say that again. The sun’s energy passes right through the air with almost zero warming, but we all know the sun warms the air. So how can this be true?

[00:05:55] Let’s start with why sunlight doesn’t warm the atmosphere. That sunlight, it’s generally visible light and also ultraviolet light. You know, the kind of light that can give you a sunburn light can be measured in wavelengths, and these wavelengths are tiny, about 280 to 750 nanometers to be exact, that’s smaller than a millimeter.

[00:06:16] And those wavelengths don’t resonate or match the vibrational energies of the molecules in our atmosphere, so they just pass right through without exciting and warming that atmosphere. For those of you old enough to remember rooftop TV antennas, you might recall that UHF antennas had shorter elements than VHF antennas.

[00:06:35] It’s the same principle at play. In order to capture radio wave energy, those antennas had to match the wavelength of the radio wave. So this visible and UV light passes through the atmosphere and eventually reaches the Earth’s surface and the surface is what actually heats up. In fact, land and hardscapes are pretty efficient at absorbing that energy and warming quickly.

[00:06:59] So I promise I’d tie this into ecology here and there. It is the surface heating principle that allows for many plants to germinate earlier in the year than you might expect. It’s why south facing slopes, at least in the Northern hemisphere, get started much earlier in the spring, the north facing slopes.

[00:07:15] And it’s also why early season ground dwelling insects, including some caterpillars, can start their life cycles early in the year. The surface temperature close to the ground can be tens of degrees warmer during the day than the air, just a few inches or several inches above. Now as the ground heats up, it causes the adjacent air to warm.

[00:07:35] But how is that? Well, the ground actually radiates infrared upwards and infrared wave lengths are actually quite a bit bigger than the visible light spectrum. They are absorbed efficiently by greenhouse gases like water vapor and CO2 that’s prevalent in the atmosphere. And as a result, the infrared warms that adjacent air. If you’ve ever thought about how hot air balloons work, you know that warmer air rises. So daytime heating can instigate lift pretty much all by itself. But before I proceed, I wanted to talk a little bit about air pressure, because that’s also important.

[00:08:11] All of the atmosphere actually exerts pressure and the air pressure is higher near the surface of the earth. It reduces as you go upwards because there’s less atmosphere above to simply push back down on you. So the lower you go, the higher the air pressure. As a result, when the air warms near the surface and rises, it expands with the altitude ’cause there’s less air pressure pushing on it.

[00:08:35] Expanding air loses energy and cools.

[00:08:39] Also, as air warms up, it means the molecules start to get more excited and they vibrate more and push outwards and the air becomes less dense. We’ll talk about that a little bit more in a moment, but, uh, that lack of density is really what causes air to take off. So if you think about this from a common sense standpoint, since the atmosphere heats from the surface first, it sort of makes sense that the further away from the surface you get the cooler it will be as air rises.

[00:09:04] As I said, it expands and cools because there’s less atmospheric pressure to compress it. So this is why mountaintops often stay snowy and are colder while valleys bake hotter than surrounding areas in the summer. So lemme talk about lift a little bit more. I just described how daytime heating can instigate lift, but other mechanisms can induce lift as well.

[00:09:25] For example, air moving towards mountains might be forced to go upwards because that mountain is blocking them. This is called Oro graphic lift for those looking for a fancy term, and it’s one of the reasons why, say, in the Rocky Mountains you get thunderstorms quite often in the summertime. Weather fronts can also force lift.

[00:09:45] A cold front, for example, represents a wedge of colder air pushing along the earth’s surface. Think of how a car moving in the highway forces air to lift up and over the roof. It’s a similar principle with cold fronts, but on a much bigger scale.

[00:10:01] So we have aura graphic lift caused by topography or mountains. Frontal lift caused by cold fronts, for example, and convective lift caused by the heating of the surface of the earth. We now know how lift works, but why is lift an ingredient for thunderstorms? So for that to make sense, we need to tie the moisture ingredient into the lift ingredient to understand this. I.

[00:10:23] So let’s imagine that air near the surface of the earth has a 70 degree dew point. As I said before, that’s pretty humid. That means there’s a lot of moisture in that air, and that air then is heated, that moisture laden air starts to rise.

[00:10:37] This could be further amplified. Say if a cold front’s approaching, forcing additional lift as it lifts, it cools, as we just described. And remember, colder air can’t hold as much moisture as warmer air. At some height in the atmosphere, that air’s going to cool to the dew point.

[00:10:53] The air becomes saturated and the water will start to condense forming clouds.

[00:10:59] Now we don’t have thunderstorms yet, but you can see how lift plus moisture starts the process with those clouds. So now it’s time to move on to the third and final piece of the thunderstorm puzzle that’s instability. Think of the atmosphere, maybe like a stack of pancakes. If the bottom pancake, the surface air is really hot, and the top pancake, the air higher up is cold.

[00:11:20] That stack of air anyway becomes unstable.

[00:11:25] As we said, hot air wants to rise, and if it’s warmer than the air above it, it’s going to keep rising. Like that hot air balloon we mentioned before. If this rising air can keep going up, it’s a perfect setup for cloud formation and potentially a thunderstorm, and this is where instability comes into play.

[00:11:41] For thunderstorms to form the air near the surface has to be warmer and less dense than the air above it. I’m gonna pause here for a moment because I just said less dense, and I briefly mentioned that before. And when I first was learning about this, I was pretty confused about what I just said a moment ago where the pressure.

[00:11:58] Of the air is actually higher near the surface, but we’re talking about this warm air near the surface being less dense. So remember that warmer air means the molecules are more excited, bouncing around and spreading out. So this is how these pockets of warming air become less dense than the air above it, allowing it to rise.

[00:12:18] These pockets of rising air, they’re called thermals and another ecological aside. These warm rising thermals are what many birds use to gain, lift and aid in their flight. It’s why you often see vultures and raptors circling in a thermal. Or using lift caused by nearby hills. It’s the same principle, and they’re smart enough to know that, you know, they don’t want to expend extra energy, so why not use all of this energy that the atmosphere provides for them?

[00:12:45] Now in this scenario, with this less dense, warm air. It means it’s going to continue to rise buoyed by the cooler, denser air around it.

[00:12:53] The more unstable the atmosphere, the easier it is for the air to rise, forming those clouds, and in a very unstable environment, it can rise higher and higher and higher forming even more towering clouds, and these clouds can grow into powerful culo nimbus clouds, which are the hallmark of thunderstorms.

[00:13:10] So in short, instability is what turns rising air into a storm.

[00:13:14] So with these three basic ingredients. Yeah, everything is there to create a thunderstorm, but you may have heard a meteorologist mention on air that you know there’s a chance that thunderstorms, but they acknowledge some uncertainty despite these ingredients because there’s what’s called a cap in the atmosphere.

[00:13:30] What is this cap? While usually air is cooler, as you gain altitude, sometimes there can be a phenomenon called a temperature inversion. In other words, there may be a layer of warm air in the middle of the atmosphere. If warming surface air encounters this cap lift might stop blocking storm development.

[00:13:50] Often it’s unclear if a cap will erode sufficiently to allow thunderstorms to form a cap might be overcome by sufficient ground heating or mixing in the atmosphere or other mechanisms. A combination of all of them. The science of temperature inversions can be pretty complex, so I’m just gonna leave that.

[00:14:08] Here for today, the fact that these caps can and do exist, and it throws a wrench into forecasting at times. By the way, there’s also a measurement for atmospheric instability, and it’s called Cape. Cape stands for a convective available potential energy, and since it’s a measure of energy, this means it’s measured in joules.

[00:14:29] The higher the cape, the greater the chance that thunderstorms can become severe with strong updrafts, which can lead to hail formation. Now, quick aside, how does hail form? Well, if there’s a strong updraft that warm air rising quickly and high up where cools, you know, just as quickly those condensed water droplets freeze, and if it cycles up further and further, more and more water can be added on creating larger and larger hail.

[00:14:56] Oftentimes within the thunderstorm, there’s a mix of updrafts and downdrafts, and you can get these hailstones going up, getting larger, then start to fall. Then they get caught in another updraft. And in these scenarios you can get really, really large hail.

[00:15:13] Now, there can’t be situations where you have only one or two of the three ingredients, but you really do need all three for thunderstorms. You can have plenty of moisture, but if there’s no lift, it would not condense to create clouds and precipitation. If there’s not sufficient instability, it may not lift high enough to create a thunderstorm.

[00:15:32] Now, there’s also situations where you can have all three ingredients, no cap, and still not get a thunderstorm.

[00:15:40] Well, let me rephrase that. You might get a thunderstorm, but it might not rain.

[00:15:44] So this unique occurrence is sometimes called a dry thunderstorm, and it might seem paradoxical because you need moisture to create clouds, but how can you not have enough moisture to lead to precipitation in that situation?

[00:15:57] So this phenomenon, it’s most common in arid areas, but it really can occur almost anywhere. And the fact that it’s more common in arid areas maybe gives you a hint as to what’s happening. Maybe a little bit similar to the temperature inversion scenario. Sometimes you end up with a scenario where the air very close to the ground is exceptionally dry, and the moisture that’s feeding into the thunderstorm might be a few thousand feet above the surface. This can still generate thunderstorms, but when they start to precipitate, the rain evaporates when it hits that narrow dry air before it reaches the ground.

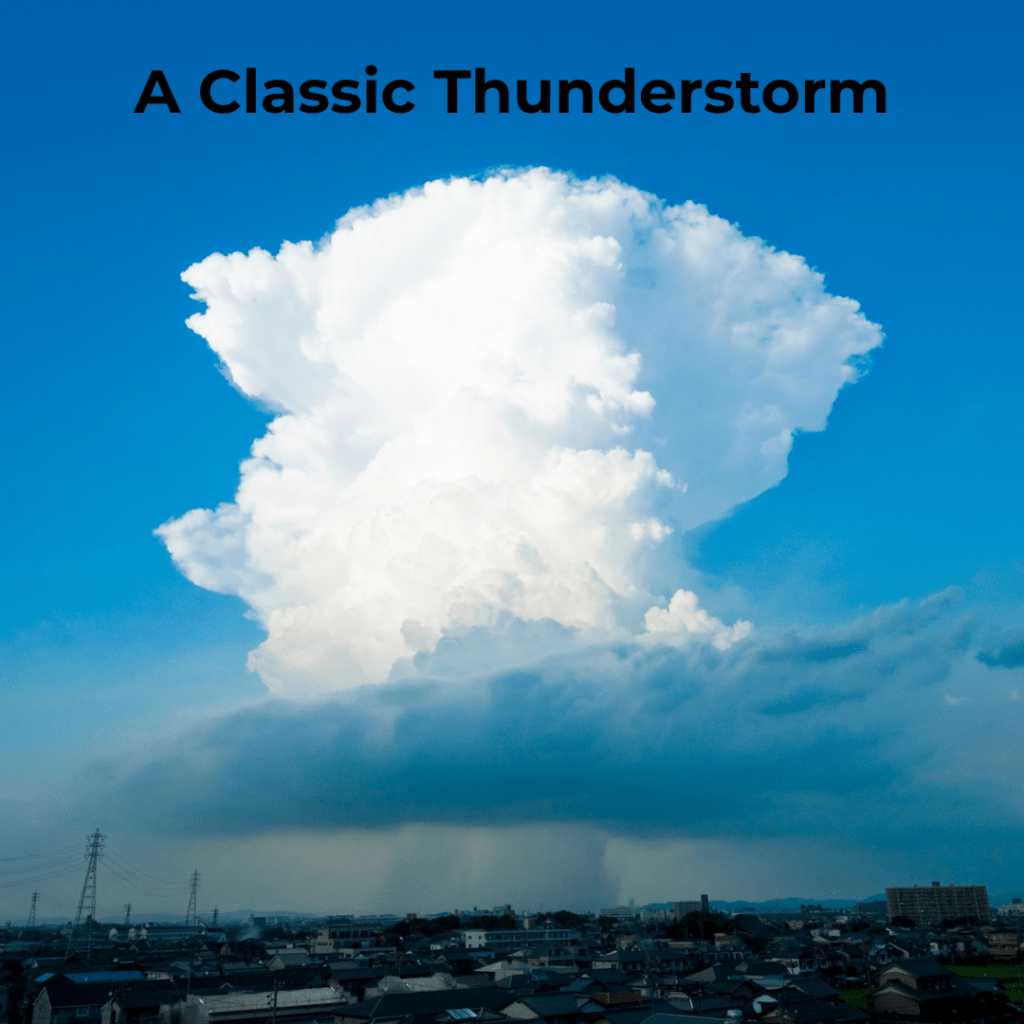

[00:16:31] Adding to this evaporative effect is that low dry air might also be very warm, and remember, warm air can hold more water so it has more evaporative potential. This phenomenon of rainfall that evaporates before reaching the ground is called virga, and you’ve probably seen it before. It looks almost kind of like ghost rain. There’s these streaks coming out of the clouds, but you don’t end up with anything more than maybe a sprinkle or nothing at all at ground level. so that’s a basic description of the ingredients needed for a thunderstorm, but what does a thunderstorm lifecycle actually look like as it forms matures and fades? So let’s walk through. A classic thunderstorm.

[00:17:09] Example, a single cell storm that’s like an individual storm that’s just developing, say in the plains or over a mountain or something like that. It starts with a cumulus stage. This is when warm, moist air rises, cools and condenses into those puffy kind of popcorn. White cumulus clouds, updrafts dominate here.

[00:17:30] The air is rising quickly, building those tall cloud towers, but there’s no precipitation yet, but it’s brewing. Then comes the mature stage as we approach the storm’s peak. The cloud has continued to grow vertically because of the instability, often punching up to the very top of the troposphere into the stratosphere sometimes, and that’s when it forms that classic kind of a anvil shaped cloud where the top of it spreads out at the boundary of the troposphere rain, and sometimes hail begins to fall, lightning flashes and the storm becomes turbulent with both those strong updrafts and downdrafts.

[00:18:06] Those downdrafts are what? Drag rain cooled air towards the ground, creating those gusty winds at the surface. The stage is pretty dramatic, the one that we experience as the thunder and lightning show. Eventually, the storm enters the dissipating stage. And this is where Downdrafts start to dominate. How can this happen?

[00:18:24] Well, maybe the moisture has been largely consumed, or the feed of warm air has been cut off, or it’s getting dark and nighttime is falling, and there’s not as much warm air to feed the storm. So the storm could also cut off its own supply of warm air. But however it happens, if you have a thermometer at home, you might notice that temperatures drop significantly in the late stages and the aftermath of a thunderstorm.

[00:18:48] The rain tapers, the lightning fades and the clouds begin to collapse.

[00:18:53] Now, most of the thunderstorms we see fall into this simple lifecycle, but sometimes, especially when there’s wind shear, storms can become more organized, forming multi-cell clusters or even rotating, that produce not only hail and strong winds, but occasionally tornadoes.

[00:19:09] So I would like to spend a minute on tornadoes. In fact, I hope to have an interview about this topic in the future. And again, things get super complex here, so I’m gonna keep it very high level. But I will say that you often need yet another ingredient beyond moisture lift and instability to get a tornadic thunderstorm.

[00:19:29] And that tornadic ingredient is wind shear.

[00:19:32] Shear is the variation in wind speed and direction with height in the atmosphere. Have you ever looked at the sky and seen clouds at one layer of the atmosphere moving in a different direction than clouds?

[00:19:43] At another layer of the atmosphere that’s shear? You can sometimes feel it too. The surface winds might be moving in a different direction than the clouds that you see. So shear adds a rotational component to the atmosphere. Shear is not as simply assessed as Cape since you could have different speeds and different directions of wind at all layers of the atmosphere. So how do you assess shear and CAPE and all these different things? Well, this, believe it or not, is still largely done with weather balloons. Weather balloons have been in the news lately because of proposed and even enacted cuts to the National Weather Service.

[00:20:18] Some politicians, if even characterize weather balloons as outdated technology, but this is not true at all. It might seem low tech since weather balloons have been used for decades, but this is a case where low tech is actually the most cost-effective way to go. Let’s make sure we’re on the same page about what weather balloons actually are.

[00:20:38] So they are large latex balloons that have sensors attached. There’s usually a box that, has things like GPS and atmospheric sensors and radios to be able to transmit their data back to the earth. They’re inflated with helium and launched from several hundred sites twice daily in a coordinated effort to characterize the atmosphere in three dimensions.

[00:21:02] As they rise, they’re measuring temperature, moisture, wind, speed, and more. This allows for direct measurement of cape and shear as well.

[00:21:11] These measurements can also help identify when there are caps in the atmosphere. All of this data is fed back into computer models that help for both short term and medium term forecasting. Without weather balloons, the accuracy of thunderstorm and severe weather forecasting will become notably worse.

[00:21:27] Radars, satellites, and computer models cannot fill the crucial gaps that weather balloons provide.

[00:21:32] Now if you have a chance of thunderstorms in your area or there’s a chance of a severe weather outbreak, one thing that I like to do and I recommend that people do is don’t just read the forecast. Go to the National Weather Service webpage. Find the weather Service office that services your area and look at what they call the forecast discussion.

[00:21:51] When you read the forecast discussion, they’ll talk about some of these things. So while the forecast itself might say a 50% chance of thunderstorms and some may be severe, when you read that discussion, you can hear about what goes into it. They might talk about how there’s a cap and they aren’t sure if that cap is going to break or not, or maybe the cap is gonna break too late in the day and the storms might get started, but there may not be enough time for them to become severe.

[00:22:16] All of those interesting details are often discussed. In the forecast discussion. So check it out when you have a chance. So that’s it. That’s your thunderstorm 1 0 1. I’d love to hear what you think. What questions do you have? What would you like to hear from expert guests on any of these topics we touched on today?

[00:22:32] Let me know at podcast@jumpstartnature.com.

[00:22:35] And if you enjoyed this weather oriented episode, I invite you to check out episode number 80 where we talk about El Nino, la Nina, and oceans in general, and how they affect the climate and weather. Also, episode number 84 is with Dr. Marshall Shepherd, a well-known meteorologist where we talk about the difference between weather and climate, and also get into thunderstorms a little bit there too.

[00:22:57] That’s all for today. Thanks so much for listening.