#126: New Hope for Sunflower Sea Stars – Nature's Archive

Summary

Some of the most consistent feedback I get about the podcast is the message of hope that rings through. Today’s episode takes the message of hope up a level by revisiting the folks at the Sunflower Star Lab.

Sunflower sea stars are amazing creatures – not your typical sea star. They can reach over three feet, live for decades, they are highly mobile, and function as keystone species in kelp forest systems. Just a little over a decade ago, there were 6 billion of these animals along the pacific coast of North America. Then, they vanished. And the consequences to kelp systems has been dire.

But thanks to innovative work at the Sunflower Star Lab, and the numerous partners that they’ve cultivated, things are looking up – and much more quickly than I ever imagined.

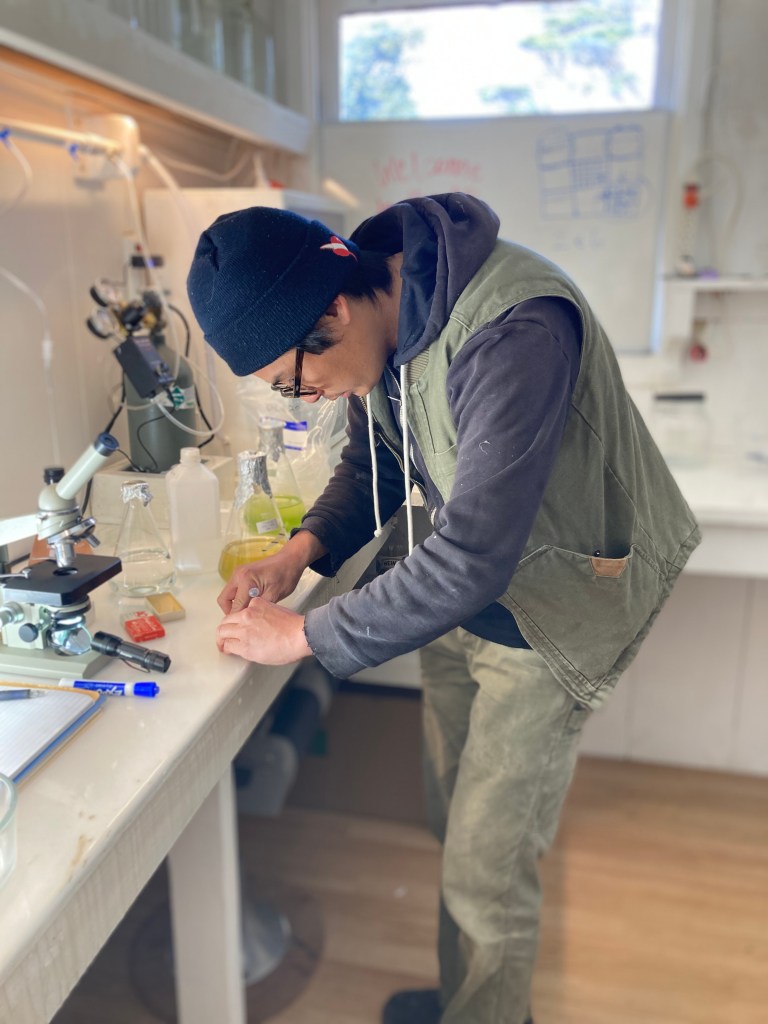

So last December I made the short trip down to Moss Landing, California, and today I’m sharing my conversation with Reuven Bank and Andrew Kim from the Sunflower Star Lab. They’re here to tell us the full story of the Seastar and why things have taken this turn for the better. You might remember them from episode 104 – even if you listened to that one, I promise you today’s episode is well worth a listen.

Check out the Sunflower Star Lab at sunflowerstarlab.org and on Facebook and Instagram.

And thanks to Brooks Neely for editing help in this episode!

Did you have a question that I didn’t ask? Let me know at podcast@jumpstartnature.com, and I’ll try to get an answer!

And did you know Nature’s Archive has a monthly newsletter? I share the latest news from the world of Nature’s Archive, as well as pointers to new naturalist finds that have crossed my radar, like podcasts, books, websites, and more. No spam, and you can unsubscribe at any time.

While you are welcome to listen to my show using the above link, you can help me grow my reach by listening through one of the podcast services (Apple, Spotify, Overcast, etc). And while you’re there, will you please consider subscribing?

Links To Topics Discussed

Credits

Editing by Brooks Neely.

The following music was used for this media project:

Music: Spellbound by Brian Holtz Music

License (CC BY 4.0): https://filmmusic.io/standard-license

Artist website: https://brianholtzmusic.com

Transcript (click to view)

Michael Hawk owns copyright in and to all content in transcripts.

You are welcome to share the below transcript (up to 500 words but not more) in media articles (e.g., The New York Times, LA Times, The Guardian), on your personal website, in a non-commercial article or blog post (e.g., Medium), and/or on a personal social media account for non-commercial purposes, provided that you include attribution to “Nature’s Archive Podcast” and link back to the naturesarchive.com URL.

Transcript creation is automated and subject to errors. No warranty of accuracy is implied or provided.

[00:00:00] Andrew Kim: I mean, it’s a rare, kind of study to pull off, so it’s kind of like a groundbreaking study for Pycnos It was like a being out there to see all that happen it was like a well oiled orchestra.

[00:00:11] Reuven Bank: And this just happened, this was October of 2025 and we just announced this publicly a few days ago. So this is very hot off of the presses kind of groundbreaking research that took place.

[00:00:22] Michael Hawk: It’s, it’s super exciting.

[00:00:23] I mentioned earlier I kind of got chills hearing about, what happens to the stars when they become infected. But same here, i’m getting chills for different reasons. Hearing and seeing your enthusiasm for this work, it is just super exciting.

[00:00:35]

[00:00:37] Michael Hawk: Some of the most consistent feedback I get about this podcast is that the message of hope rings through today’s episode takes that message of hope up a level by revisiting the folks at the Sunflower Star Lab. Sunflower Sea stars are amazing creatures, not your typical sea star. They can reach over three feet live for decades.

[00:00:58] They’re highly mobile and they function as a keystone species in kelp forest systems. Just a little over a decade ago, there were 6 billion of these animals along the Pacific Coast of North America. Then they vanished, and the consequences to kelp systems has been dire. But thanks to the innovative work of the Sunflower Star Lab and the numerous partners that they work with and that they’ve cultivated, things are looking up and much more quickly than I ever imagined.

[00:01:26] Last December, I made the short trip down to Moss Landing California, and today I’m sharing my conversation with Reuven Bank and Andrew Kim from the Sunflower Star Lab. Andrew is the laboratory manager, and Reuven is chairman of the board and along with a few others, they are co-founders of the Star Lab.

[00:01:43] They’re here to tell us the full story of the Sea Star and why things have taken this turn for the better. You might remember them from episode 104. Even if you listen to that one, I promise you today’s episode is well worth the listen. You will walk away excited and inspired. So without further delay, Reuven Bank and Andrew Kim.

[00:02:04] Reuven, Andrew, thank you for joining me yet again.

[00:02:07] Reuven Bank: Thanks so much for having us.

[00:02:08] Yeah, we’re excited to have you back in Moss Landing. Thanks for coming back.

[00:02:10] Michael Hawk: Yeah, well, I’m really excited about this because you reached out about some exciting news that we’re going to get to in the course of the conversation, and I, I’m just kinda like bursting to talk about it. So we’ll get there.

[00:02:24] But we’re talking Sunflower Sea stars and we did what, a year and four months ago about, we, uh, had another episode about the work you’re doing at the Sunflower Star Lab. So I will refer listeners to go back to that one, to get the baseline of what we’re talking about today. But I do think it’s important to maybe refresh a little bit on what is a Sunflower Sea Star, how they fit in the ecosystem and why you exist as an entity.

[00:02:54] So maybe we can start off with a refresher on Sunflower Sea Stars. What are they?

[00:03:00] Andrew Kim: Yeah, Where to begin? I mean, they’re just like an extraordinary, weird, and amazing organism. They’re one of the largest and fastest species of sea stars. They’re extremely abundant. It’s subtitle, environments from Alaska to Baja, which is their kind of historic range, occurring from the intertidal out to about a hundred meters.

[00:03:22] And they are just these amazing, predators that cruise around in the bottom with very, relatively, long pelagic larval duration, they’re broadcast spawners. They have amazing regenerative abilities. It’s hard to pull all of the cool things out of the ether from nowhere that go into the history and life history and biology of

[00:03:46] Michael Hawk: This is part of what I love about the podcast. I get to ask these challenging questions across so many different species and environments.

[00:03:53] Reuven Bank: For your,

[00:03:54] For your listener who is just hearing us talk, it might easy to picture, like some versions of sea stars. You might see in popular culture like Patrick from SpongeBob, or perhaps they’ve gone tide pooling and seen an ochre star or a bat star in a tide pool and sunflower stars, also sea stars, they’re Asteriids and related to those sea stars that you’d see, are also really different in very tangible ways.

[00:04:20] They look different, they feel different, they move different. Sunflower stars grow way bigger than most other sea stars. They have way more arms.

[00:04:29] Michael Hawk: And how big is that?

[00:04:29] Reuven Bank: The topic of how big a sunflower star can actually grow. It’s a little bit up for debate over three feet is what we generally say. If you see them all stretched out, there’s one I believe at the Vancouver Aquarium that’s been estimated to be like four feet plus potentially. And they can live for so many decades that it can be difficult to exactly pinpoint how big can a Sunflower star get? Yeah, so they can be massive. They can move over a meter per minute. You can watch them crawl along the bottom. If you’re a diver, we’ve heard from researchers who go diving, they see a sunflower star, they go change their tank, come back down, it’s gone out of their field of view. It moves so fast, which is maybe different to perceive then if you’re just tide pooling and you see a sea star you’re used to seeing just clinging to the same rock.

[00:05:15] It seems almost like a sessile animal if you see it kind of on a human timescale. But sunflower stars are also really soft compared to other sea stars. They’re covered in papulae, which are almost like gills, for a sea star, promote gas exchange. They are brilliant colors. Everything from pink to green to blue to purple, to orange. Most of our stars have turned very purple. It’s been exciting to see how many of their siblings are also different colors.

[00:05:45] Michael Hawk: Is that driven by diet or genetics?

[00:05:47] Reuven Bank: Andrew’s got a pet theory.

[00:05:48] Andrew Kim: Kinda, yeah. Yeah. A little hair brainin theory, but it’s probably a bit of both. Mm-hmm. Okay. Yeah, some combination of genetics and the environmental and other things that occur over the course of your life, whether it’s diet or, maybe exposure to sunlight.

[00:06:02] Michael Hawk: So what I’m hearing is it’s just this is a phenomenal animal in that unlike most sea stars, it’s much bigger. It moves faster. You said it was a predator. I understand it’s a keystone species as well. Can you tell me a little bit about how?

[00:06:15] Andrew Kim: Yeah. And also, I think lots of sea stars are predators, but this one is special as you mentioned in that they’re keystone species.

[00:06:22] And I also, I don’t think that we mentioned yet that they are a multi-armed star with up to 24 large arms. I just kind of started like spitting out facts. But, yeah, that’s a really important one. The more and very distinctive.

[00:06:36] Michael Hawk: And most sea stars have less than 10 or something like that.

[00:06:39] Andrew Kim: If you picture most people, you know, you picture your classic sea star, you’re gonna see this five arm, Patrick from SpongeBob, type star but this is very distinctive in the just number of arms. And as Reuven was saying, like their kind of soft bodiedness, allowing them to get into all the cracks and crevices and really race across the reef.

[00:07:02] Michael Hawk: So they’re fast so they can potentially chase prey?

[00:07:05] Andrew Kim: Yes.

[00:07:06] Michael Hawk: And they can squeeze into crack. So can they do kind of lie in wait predation as well?

[00:07:11] Andrew Kim: I don’t know if you can go as far as saying that they’re doing, you know, like whatever the definition exactly of lie in wait predation might be, but I’ve seen the Pycnos, like at least in our facility, kind of look like they’re pouncing on an urchin, kind of like getting there, lining themselves up and then going in for the kill.

[00:07:32]

[00:07:32] Michael Hawk: I do realize I diverted,

[00:07:34] I asked about, you know, tell me about how they’re a keystone species, what effect do they have on the ecosystem? And then, then I started asking additional questions.

[00:07:40] So, so it’s all good.

[00:07:42] Andrew Kim: Sunflower stars are really important animals. We talked about how they’re incredibly cool, but they’re also, very important for the health of kelp forest ecosystems and other nearshore marine ecosystems. Sunflower stars live in a lot of different places. Historically, they were found in a range from Alaska down to Baja, California with higher abundance towards the northern edge of that range.

[00:08:07] And they eat a lot of different things in addition to living in a lot of different places. They can scavenge, they can directly predate on all kinds of different marine organisms, but they were really important because of the role they had in keeping populations of grazers in check. Sunflower stars are really good at eating urchins and other grazers, and they’re also really good at scaring them.

[00:08:31] They create a landscape of fear on the ocean floor where everything and studies have shown up to 16 feet in every direction will smell them coming and take off running for the hills. And that’s an important impact that they have both by eating species like urchins, which are native grazers in the kelp forest, as well as scaring them because they can keep those populations in balance and keep them from overgrazing on kelp.

[00:08:56] So in a balanced kelp forest ecosystem, you have grazers like purple urchins doing their part in the kelp forest and sunflower stars predating on them, and scaring them, and keeping them in check. And so that’s a really important role because those keystone predators, even though they’re not as abundant in mass as say the kelp around them or the urchins, they still have an outsized impact on the ecosystem around them because of their ability to scare and eat the things that eat the kelp.

[00:09:23] Michael Hawk: Yeah, there’s analogies, I guess, to terrestrial systems. The apex predators, by biomass are usually quite small, but it’s that landscape of fear effect that really causes that outsized impact. are they truly an apex predator or are there predators of sunflower Sea stars?

[00:09:43] Andrew Kim: There are predators. Some large crabs can take down sunflower stars. They have a pretty good, defense mechanism in that they’ve got 24 arms, you can drop an arm, and feed a crab, and run in the opposite direction and be fine. There is a species of star, Solaster, which is a star that occurs mostly Pacific Northwest and north.

[00:10:05] And they predate exclusively on other sea stars, including Pycnopodia, and Pycnopodia have a pretty strong fear response to the presence of Solaster.

[00:10:15] Reuven Bank: Solaster, or the Dawson Sun star, is actually smaller at its largest length than the Sunflower Star. But Sunflower stars do have that fear response and most predatory attacks would involve like an arm being taken.

[00:10:27] We’ll keep this anonymous as to which aquarium mentioned this but, pre seastar wasting disease, when sunflower stars were extremely abundant there were aquariasts who were pulling up so many sunflower stars in, some of their catches, that they would put them in exhibits with king crabs as food for the king crabs and watch them in a confined space where they couldn’t run away and drop an arm become a meal for the crabs.

[00:10:51] Down here, especially where we are in central California, there’s been documented cases of otters taking like an arm of a sunflower star towards the southern limit of things like the Dawson Sun Star, but they’re primarily not being eaten by very much around here, including humans who have no interest in munching on them.

[00:11:08] Michael Hawk: And I suppose as is always the case when we’re talking ecology, biology, there’s never hard and fast rules, right? So there’s always these gray areas. And then the other thing I was realizing as you were describing this to me is it’s easy to imagine the full adult sized animals that you’re talking about, the king crabs, the sea stars, but in reality, there’s a significant period of time where the sea stars are quite small.

[00:11:30] Andrew Kim: Exactly, yeah.

[00:11:31] Michael Hawk: And that’s a whole different dynamic than during that phase.

[00:11:33] Andrew Kim: Mm-hmm.

[00:11:34] Michael Hawk: So that, that, that makes sense. So here we are, we’re in Moss Landing, Central California. It’s an amazing area. I’m gonna bite my tongue and not go off on a wild tangent about why this is such a cool area.

[00:11:45] But for people listening, if you know where San Francisco is and where Monterey is, kind of in that region closer to Monterey. And if we could say 20 years ago, if somebody is diving in this intertidal range, you set out to about a hundred meters, what’s the likelihood they would see a Sunflower Sea star?

[00:12:05] Andrew Kim: You would’ve probably seen at least one Pycnopodia on a kelp reef diving around. They were extremely abundant, one of the most abundant subtitle species and, very conspicuous.

[00:12:15] I think, you know, it’s kind of for that reason that they were overlooked, that they just kind of were everywhere. And I have very vivid memories of, diving at the wharf, and it was like the wharf was crawling with Pycnopodia in Monterey. Yeah, we had down here lots of very big, Pycnopodia, you know, not quite in the density and abundance, that you would find up in say, Alaska, but definitely lots.

[00:12:40] Michael Hawk: So I had read, and I think we talked about this on the first episode, that peak population estimates were there were about 6 billion of these sea stars. And now if we fast forward to today, just to kind of paint a contrast, if someone were diving in a kelp forest, say around Monterey, when was the last time that there was a wild sunflower sea star seen?

[00:13:05] Andrew Kim: 2018 at the Breakwater, I think is the last observed Sunflower star that I’ve heard of.

[00:13:11] Reuven Bank: Yeah. By Pat Webster, friend of the lab. Pat Webster. Shout out to Pat. Yeah. An incredible underwater photographer.

[00:13:17] We’ve had occasional reports of things that might be sunflower stars in the general central California area. I think a lot of them have turned out to be things like very large, giant spine stars or people see a large sea star. So the last confirmed sighting was 2018 on breakwater wall. Northern California does have occasional sightings, really starting like 2021, there were a handful seen every year.

[00:13:42] And then that has increased a little bit, but they’re still functionally extinct across, Northern California, Southern California and central. They used to be abundant on the reef. These brilliantly colored, massive sea stars have just vanished almost overnight and have not come back where you could go diving every day for a year and not see one here in Monterey.

[00:14:03] Michael Hawk: So what happened? Why did they vanish?

[00:14:06] Andrew Kim: Starting in 2013, there was a disease which we now know is caused by a bacterium, Vibrio pectenicida or VPEC for short, basically melted sea stars from Alaska to Baja and almost seemingly overnight laid waste to billions of sea stars and Pycnopodia, were the first to go and the hardest hit. You know, When they disappeared that was very alarming. But not everyone was necessarily knew kind of what the ecosystem consequences would be.

[00:14:39] Michael Hawk: And you said this happened kind of overnight. I remember reading and hearing from you previously about the sort of the dramatic visual of Pycnopodia that was infected with sea star wasting disease.

[00:14:50] Can you tell me a little bit about, I, I, I know it’s a little gory, but what actually happens there?

[00:14:55] Andrew Kim: Yeah. It’s a very rapid progression of symptoms. You can have apparently healthy stars basically rip themselves up, crawl in opposite directions, and melt into basically piles of white goo in a matter of 48 hours, in some cases.

[00:15:13] And so it’s a, it’s an extremely rapidly progressing disease, which is yeah, just another reason why I think it was very difficult to, to study because this is an event that’s occurring, maybe in terms of a disease, you would think that you would have a little bit more time to get your things together to, to try to capture data and understand what’s happening.

[00:15:34] But it, in the case of Pycnopodia, it was just like, that was it. They were gone.

[00:15:39] Michael Hawk: Yeah, just it gives me chills, just visualizing that and then knowing the impact that happened. And this just swept across populations in a course of a couple years, handful of years.

[00:15:51] Reuven Bank: outbreak began in 2013, was likely exacerbated in the following years by a extreme warm water event, often referred to as the blob that was at its peak from 2014 to 2016.

[00:16:04] The scale of this can’t really be overstated. We’re talking about perhaps the largest marine disease outbreak on record. Over 20 different species of sea stars were impacted by this, perhaps none as strongly as sunflower stars. The impacts of this have cascaded down thousands of miles of coastline.

[00:16:21] Michael Hawk: And you alluded to the impacts to the ecosystems, the kelp forest. Can you tell me a little bit about, what was seen as the Pycnopodia disappeared Yeah. and what’s seen today,

[00:16:33] Andrew Kim: In some areas, particularly I’m thinking about Northern California and our bull kelp forests because maybe some of your listeners will have heard about the 95 plus percent kelp declines over the last decade in Northern California, and that’s really due to this sort of triple whammy of sea star disease, urchin overgrazing, and the marine heat waves that have stressed the kelps in these places that do not have trophic redundancy, meaning there aren’t other sea urchin or grazer predators, the sea urchins just crawled out and, mowed down these kelp beds. And in the case of bull kelp, which is an annual species, the bull kelp needs to go from being a spore to releasing spores annually to have this perpetual production, complete the life cycle.

[00:17:18] Yeah. And complete the life cycle. and, uh, If you have lots of urchins out and about marauding on the reef, not suppressed in the landscape of fear, you can really have these just persistent, barren states off the northern California coast.

[00:17:32] You have, hundreds of miles of in many, stretches of contiguous reef, that are, spine to spine urchins in a lot of places.

[00:17:40] Michael Hawk: I’ve seen photos of kelp with literally, I mean, dozens of urchins all over it. And you can really, when you see these pictures, you can see why and how quickly that impact can occur.

[00:17:52] Reuven Bank: Yeah, it’s a clear cutting. In many cases, it’s almost comparable to deforestation in the Amazon, looking at a vibrant jungle one day, and you come back and there’s nothing but a raised field, covered in, in some cases, millions of these spiny, kelp grazers. And the decline is different along different parts of California.

[00:18:13] Northern California, according to the 2024 kelpwatch.org report card lost 97% of its kelp over the last decade. The Monterey area has lost 80% of its kelp. Southern California has trophic redundancy, especially within marine reserves with lobsters, sheephead warmer water species who like to eat urchins, but in places that don’t have significant amounts of those predators, you’re seeing urchin barrens as well, especially Santa Rosa and San Miguel Islands where sunflower stars were historically common.

[00:18:44] It’s the cold water temperature down in the channel islands on the western end of that stretch losing sunflower stars has led to massive declines, equivalent to almost northern California. So you’re seeing it across different areas where, you might be hundreds of miles away from the Northern California kelp decline, but you lose sunflower stars on those islands and the same impacts happen to the ecosystem.

[00:19:04] And you go from some of the most vibrant kelp forest ecosystems on the planet to barons with millions of urchins covering rocks. And it’s a almost like a ghostly site to see.

[00:19:16] Michael Hawk: So then. In the midst of all of this, the Sunflower Star Lab started and we get pretty deep into the origin story in the first episode.

[00:19:27] So I will point people there for the full story, but for context, which I think that’ll be helpful for where we’re going next. When, when did the Sunflower Star Lab begin and what was that initial vision?

[00:19:40] Reuven Bank: Almost four years ago to the day. We started in December of 2021. The original vision, came from Vince Christian, who we call our star father, a local Monterey resident, retired water quality engineer, who was an avid diver for decades in Monterey.

[00:20:00] And like Andrew would see sunflower stars on the reef and also witnessed the effect of what happened when they were gone his favorite dive sites, in some cases turning into urchin barren. So he went up and visited Dr. Jason Hodin at Friday Harbor Laboratories at the University of Washington, the first laboratory to complete the lifecycle of a Sunflower star in an aquaculture setting, and decided, Hey, maybe we can do this down here, put out a Facebook post.

[00:20:26] That got a remarkably well-suited panel of potential, um, co-founders to join this effort and start a nonprofit dedicated to researching, restoring the Sunflower Star in our state.

[00:20:39] Michael Hawk: so you’re actively growing Sunflower stars in the lab right now, and we talked about that previously in the last 16 months or so since we last spoke, how has that operation progressed?

[00:20:53] Reuven Bank: It’s progressed in a number of ways. The stars are a lot bigger than when you last saw them. ,

[00:20:57] Michael Hawk: I’m hoping to see some of the same ones.

[00:20:59] Reuven Bank: We’ll revisit the stars and you’ll see how big they’ve gotten. They first settled at about half a millimeter, and so they’re roughly 500 times larger than when they first settled.

[00:21:10] Just this pretty fast growing species for a marine invertebrate. But our lab has progressed in a bunch of different ways. Physically our footprint has increased within the laboratory space. We’ve built out new additional systems. We’re growing more stars, and we’ve also expanded our research capacities.

[00:21:28] Really applied aquaculture research to better inform Sunflower star recovery and make it easier to grow sunflower stars, to monitor sunflower stars and to bring back.

[00:21:40] Michael Hawk: I think I didn’t stress this well enough in the first episode, but a lot of what you’re doing in terms of the aquaculture side, it’s groundbreaking. Can you tell me a little bit about how it’s different and some of the new ground that you have been able to cover in this endeavor?

[00:21:55] Andrew Kim: Yeah, not a lot of echinoderm aquaculture facilities out there in general it’s a pretty niche thing. so, you know, kind of Every day that we are here growing sunflower sea stars, it is groundbreaking to some degree, but the fact that we’re not only growing, a species of echinoderm, we’re growing a a predator with a complex life history, requires, pretty niche aquaculture systems and designs. And yeah, we’ve gotta grow the predator, then we’ve gotta grow the food to feed the predator, and then you’ve gotta grow the food to feed the food. And so it’s a whole like multi trophic, endeavor. And so we’re learning every day and, we’re having to design and build new systems and new protocols and ways to do the aquaculture, which is going to be a very critical tool for reintroduction going forward.

[00:22:48] Michael Hawk: And as I understand it, you’re working closely with many partners, so I imagine that you’re able to collaborate, share findings, and you’re building this sort of ecosystem of facilities that are helping in this endeavor as well.

[00:23:01] Andrew Kim: Totally. And yeah, Friday Harbor Labs being one of them.

[00:23:05] Luckily we have folks like Ashley Kidd, on the team who had a career in the public aquarium world which there’s so much pioneering and cutting edge stuff happening in the aquarium space. And we are lucky to have a lot of aquarium partners that we work with.

[00:23:21] Reuven Bank: Yeah. Sunflower Star Laboratory doesn’t just grow Sunflower Stars. We coordinate their recovery across North America. Ashley, one of our co-founders, superstar, star staff at the lab, was a founding member on behalf of Sunflower Star Laboratory of the Association of Zoo and Aquariums Saving Animals from Extinction Program for Sunflower Sea Stars, which has unlocked all sorts of avenues for collaboration with partners on everything from very specific research that’s only being done at select institutions across the country to increasing the capacity of new institutions to take on either brood stock or juvenile sunflower stars to widen the number of institutions participating in the project.

[00:24:06] So collaboration has been key to what we do, and it’s. Especially as a community-based nonprofit. We didn’t exist four years ago. There was no Sunflower Star laboratory. There was a guy in Pebble Beach with a garage and a bunch of people who wanted to help. And we’ve turned into this supercharged force for bringing this species back in part by embracing those strategic partnerships and trying to work with everybody because there are so many different people in the kelp forest conservation game, in the aquaculture sphere.

[00:24:38] And being able to utilize everyone’s specific knowledge and skillset makes the broader collaborative efforts that much more effective.

[00:24:47] Michael Hawk: The reason that I’m here today is because there’s been a lot of exciting advancements since the last time we spoke, some exciting research. And maybe I’ll leave it open-ended because I know there are multiple prongs to what’s transpired. But tell me a little bit about some of the research that has borne fruit since we spoke last.

[00:25:06] Andrew Kim: It has been a busy, busy year and some change to say the least.

[00:25:12] Reuven Bank: Sunflower Star Laboratory has a really active research component to our work. Before Sunflower Stars disappeared, there was some research and studies mostly in the field rather than in the laboratory about the species.

[00:25:25] But it wasn’t until they’re gone, people realized how important they were. And we witnessed the devastating impacts to kelp forests that people began exploring more restoration focus research into sunflower stars. And a lot of that is happening at Sunflower Star Laboratory for the very first time. If you’ve never tried to save a species before, you probably have to develop all sorts of new ways to go about, furthering those efforts.

[00:25:47] One of them is development of eDNA assay, in partnership between Sunflower Star Laboratory, Dr. Zack Gold at noaa, and other partners where eDNA or environmental DNA can be used as a tool to monitor sunflower stars or other species without actually seeing them. A lot of marine organisms are really cryptic.

[00:26:08] You might see an adult sun flower star on a dive, but especially most just like Evasterias. Good luck finding some of the really small juveniles in the reef, but many marine and terrestrial organisms were all sloughing off little bits of ourselves and uh, that environmental DNA can be picked up by taking water samples or monitoring the environment around where a Sunflower star might be.

[00:26:33] As a result of that partnership between noaa, SSL, UC Merced and others, a tool was developed where you can just take a sample of water and tell is a sunflower star in the immediate area. A lot of novel research has been going on at the lab and in the field to try and further calibrate that tool to determine how well you can actually pick up those stars at what distance, potentially even in the future if the tool works really well.

[00:26:59] Having some level of correlation between biomass of sea stars and the amount of sloughed eDNA content that gets picked up. So it’s a brand new research tool for sunflower stars that’s cutting edge to make it way more efficient to monitor them, be able to monitor them over a wider scale, and we’ve already been deploying this in the field.

[00:27:19] Across, hundreds of miles of California in partnership with Dr. Sarah Gravem at Cal Poly SLO. As well as, some very helpful benefactors with a yacht on a project called Galaxy Quest, where we’ve been going up and down the California coast taking those eDNA samples, including recently off of the Matterhorn Pinnacle, 300 feet down in partnership with Channel Island’s National Marine Sanctuary.

[00:27:43] Michael Hawk: So can you walk me through, process just a little bit? So you mentioned it’s an assay. Do you have to actually go back to a lab to apply it or can it be done in the field, like on the yacht or even maybe even closer to the measurement site?

[00:27:56] Andrew Kim: Yeah. So this is all very, very new stuff. Right now there are lots of water samples that have been collected and filtered. So there’s a lot of filters sitting in a number of freezers up and down the state. And then still awaiting further processing and analysis.

[00:28:11] So the big breakthrough and just how rapidly everything has been progressing has been wild to see. And personally it’s been like a crash course in eDNA, like the world of eDNA, over the last six months for me. But went from basically, yeah, there was some AZA Pycnopodia safe funding that allowed for the development of this assay, which turned out to be like a home run smashed because apparently, you know, Pycnopodia have large areas of their genome that are very unique to Pycnopodia.

[00:28:43] And so Zack Gold was able to just do this very quickly, relatively, in the span of weeks rather than months to years. And so on the heels of having this Pycnopodia specific assay, we were able to spin up a lab study here in the lab where we took known biomass of Pycnopodia, put them into known volumes of seawater. And this was in collaboration with Dr. Ali Beam and her lab and her postdoc, Megan Shay at Stanford, where they have, a D-D-P-C-R machine.

[00:29:14] We pulled off a study where we took the stars, put ’em into falling into the water just to look at how much juice, they’re like DNA juice, they’re pumping out relative to biomass and then looking at how that DNA degrades in relation to sunlight. And so having in the light versus in the dark bags of juice. And when we walk through the lab, I’m gonna show you my favorite piece of art in the lab, which is related to the collection of these water samples.

[00:29:40] So the lab study’s basically going to refine the eDNA tool to take it beyond just the presence, absence, that we can get with the base assay to help to paint a picture about, just how to better interpret this data.

[00:29:53] Mm-hmm. And like maybe say something about the abundance and proximity of sunflower stars. And we’ll kind of get into the next in water experiments that we did with the eDNA stuff.

[00:30:04] Reuven Bank: That’s one of the big impetus behind this work. And there’s also other really novel and groundbreaking research happening at the lab. We’ve worked with the San Diego Zoo and Wildlife Alliance, as well as Aquarium of the Pacific for the first time ever in a larval sea star freeze, a larval sea star, down at San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance with their crab preservation team.

[00:30:27] Then have it shipped up here to Sunflower Star Laboratory, where it was thawed reanimated, and then successfully settled into juveniles. This was done with giant pink stars who were also hit hard by sea star wasting syndrome. They have a, an analogous lifecycle in many ways to sunflower stars as a test case before we plan on moving on to sunflower stars with this tool.

[00:30:48] But having the ability to freeze larvae and create a biobank of frozen larva sea stars allows us to preserve the genetic diversity of this species across institutions to more efficiently start cultures, to start cultures during the time of year when you want to start settling them versus when they decide to spawn on their own.

[00:31:08] So it’s really important step towards increasing the capacity of institutions to do this research and just preserving the species in general.

[00:31:17] Michael Hawk: Do you have a sense of how long you can retain a cryogenically preserved sea star?

[00:31:22] Andrew Kim: Theoretically. Indefinitely? Yeah. You can just freeze them away, biobank them. It’s like a seed bank.

[00:31:28] And as long as the lights can stay on at these facilities, they can have little vials of hundreds of larval sea stars. Pycnopodia sperm, for example, has been biobank already. And Jason Hodin up there has a cohort of stars. He calls them the star sickles where they’re a cohort that are from frozen sperm and fresh eggs. And I guess the thing in the cryobiology world, sperm is easy, eggs are difficult. And then in our case, what we’ve learned is that larvae are actually pretty easy to do, relatively.

[00:32:04] and yeah, Having the larvae is really cool because these spawning events are really difficult to coordinate and they take a lot of effort and you don’t necessarily know, if you’re gonna get sperm eggs. And so having this extra sort of ability to bank away opportunistically, these spawning events is really, really cool.

[00:32:26] Reuven Bank: One other really important scientific breakthrough that didn’t happen at our facility, but was completed by our partners was the identification of Vibrio pectenicida, a particular strain of that bacteria as a causative agent behind sea star wasting disease. This was a huge collaborative effort between the Chi Institute, university of British, Columbia, Friday Harbor Laboratories, and many other partners. But we had 10 years of almost a complete gap in the knowledge base of what actually caused the 2013, 2014 wasting outbreak.

[00:33:02] And their study really methodically and comprehensively proved that Vibrio pectenicida is a really strong causative agent behind the disease, and that it can move between shared water of different species of sea stars between the coelomic fluid or the internal juice of the sunflower stars and other species transferred between each other.

[00:33:22] So understanding what bacteria was potentially causing an outbreak like this was really important for better understanding how to plan recovery efforts. And it also helped set up a lot of groundbreaking field work that we completed this October for the first time in history, putting Sunflower stars back in pods into the ocean here in California to test their survivorship, as well as the efficacy of those eDNA tools that we’ve developed in the field.

[00:33:53] Uh, They were later retrieved back into the laboratory, but this was a, a really large partnership led by Sunflower Star Laboratory in collaboration with the Monterey Bay Aquarium, Stanford University, the Nature Conservancy, Cal Academy of Science as a reef check and other organizations to take the first step towards the actual out planting and restoration of this species from a research perspective. And Andrew was involved heavily in experimental design and growing the stars for the lab and the field work.

[00:34:21] Andrew Kim: Yeah. And I should clarify. The, Pycnopodia out planting and research has already been occurring led by Jason Hodin’s lab.

[00:34:30] They’ve been doing it up in Washington for a couple of years now. And so this is the first time though that it’s happened in California. as Ashley likes to say, our stars went out to Camp Ocean and returned. And um, one of the preconditions to putting the sea stars out was for them to get test results So we took coelomic fluid samples, we basically the sea star blood, if you will, and sent them in to the Department of Fish and Wildlife where the, they were able to check for Vibrio. We had to get the negative back on that before we put the stars out for this experiment. Thankfully the stars got their clean bill of health, went out to the camp Ocean and we’re actually still waiting on the results from the post removal samples. But it sounds like for the most part they’re clear.

[00:35:17] Reuven Bank: Well, we don’t have all the pathogen testing results back. The survivorship results were very positive. Yeah. 47 out of 48 of the stars temporarily out planted during the survivorship trial returned from the ocean healthy.

[00:35:30] Michael Hawk: How long were they out there and what kind of containment were they in?

[00:35:34] Andrew Kim: So we had two studies that we pulled off. The first was an week long eDNA study where 12, Pycnopodia were put into what are commonly used, oyster aquaculture baskets. And we did this study on the east side of the commercial warf, Monterey, working with the City of Monterey to get the adequate approvals to use this row of decommissioned mooring blocks, which are basically these meter by meter blocks just sitting in the sand separated by about 30 meters. But we put 12 Pycnos in a single cage, fixed them to the mooring, and used a group of free divers to collect near simultaneous samples going out a hundred meters in Cardinal directions at a bunch of different points, from zero to a hundred, to look at the DNA from a point source and to investigate the detection limits of the eDNA tool.

[00:36:27] And so, that paired with in water, velocity and temperature and all that sort of data will help paint a picture about how much DNA, you know, that combined with the lab study that we did, of course, will help to inform sort of how DNA, their eDNA moves around, what the detection limits are.

[00:36:48] Michael Hawk: Is that analysis still ongoing?

[00:36:50] Andrew Kim: That’s ongoing. And so the lab at Stanford is currently working up that data, so, yeah, it was 12 stars in a cage for a few days, and then we pulled the stars out and then continued to take the samples to see how long the stuff sticks around.

[00:37:05] Mm-hmm. So that was part one. And then part two was a survivorship study and partnership with the Cal Academy, where we put stars from our facility, so 24 stars from SSL, 24 stars from Academy of Sciences, out there in a bunch of different cages to look at kind of any differences between stars that were raised at our facility, which is filtered natural seawater versus Cal Academy stars, which have been raised in strictly artificial seawater their entire lives. And I’ll say it’s really interesting the two stars are just very distinct and different depending on how they’re raised, but-

[00:37:43] Michael Hawk: visually?

[00:37:45] Andrew Kim: Visually, yeah, I think sort of behaviorally too, really. And then you, you can, I mean, we did a lot of star handling and they just feel different too.

[00:37:53] Yeah, I mean, and just to reiterate what Reuven just said it was extremely successful. Yeah, we had them out there for about a month and stars went out, 47 came back. The one star that did not come back, we suspect was lost due to cannibalism, unfortunately. We do have the arms that we found remaining Oh.

[00:38:16] That are are preserved and we’re gonna be shipping those samples out in the next few days here.

[00:38:21] Michael Hawk: I do recall you had a star in the lab named Hannibal. Yeah. And we had a whole discussion about the cannibalism. Yeah. Hannibal is a

[00:38:29] Andrew Kim: thing. Yeah. Yeah.

[00:38:30] Reuven Bank: And this was a research project to aid future restoration efforts, but there was a potential where we would put these stars out and we’d come back and they had turned into goo as a result of wasting.

[00:38:43] So it’s very promising that we were able to see this high level of survivorship. Amongst the cohort, but we were approaching this from a research perspective to better inform potential recovery efforts in the future. So there was a lot of unknowns going into this. How would this work? We had protocols in place for what levels of signs of stress would necessitate pulling the stars out of the water and ending the experiment early.

[00:39:08] But it was completed. We saw really healthy stars and great survivorship and potentially have some really cool eDNA study design results to to get back that i’m not familiar with a similar eDNA project, like as specific to what we’ve done here. No,

[00:39:25] Andrew Kim: I mean, it’s a rare, kind of study to pull off, so it’s kind of like a groundbreaking study for Pycnos and a groundbreaking study for just in eDNA ’cause when do you get the opportunity to design an experiment where there’s zero of something in the field and then introduce a single point source of eDNA. And so that’s gonna be really cool. And then, the deployment of free divers as a method for eDNA sample collection is totally novel and I think worked insanely well.

[00:39:52] Michael Hawk: And there’s sort of a community, right? Like, rewatch has a lot of divers recheck. Yeah.

[00:39:58] Andrew Kim: And so they were great in getting the free divers together, there’s 31 divers total.

[00:40:03] Michael Hawk: So that’s something that could potentially be scaled that I imagine to other areas.

[00:40:06] Totally, yeah.

[00:40:07] Andrew Kim: And yeah, and I think that there are lots of areas of the coast that you know, it’s really difficult to like schlep down the side of a, of a trail with all your dive gear and do sample collection, but you know, it’s pretty easy. You can send free divers and possibly access and monitor areas that are traditionally more inaccessible on our rugged coastline. And then just the simultaneous sort of sample collection was really, really cool. It was like a being out there to see all that happen it was like a well oiled orchestra.

[00:40:39] Reuven Bank: And this just happened, this was October of 2025 and we just announced this publicly a few days ago. You’re the first journalist we’re talking to about this. So this is very hot off of the presses kind of groundbreaking research that took place.

[00:40:52] Michael Hawk: It’s, it’s super exciting.

[00:40:54] I mentioned earlier I kind of got chills hearing about, what happens to the stars when they become infected. But same here, i’m getting chills for different reasons. Hearing and seeing your enthusiasm for this work, it is just super exciting.

[00:41:06] Maybe you can tell me a little bit about what’s next. You’ve hinted at a couple things you’re gonna get the results of the eDNA study and a few other things, but you know, what’s on your radar coming up?

[00:41:16] Reuven Bank: A lot of stuff is on our radar across many facets of Sunflower Star recovery. Each of the types of research we discussed have kind of iterations to help refine them and answer better questions, in terms of cryo-preservation, getting through additional cryo trials with giant pink stars before potentially moving on to sunflower stars.

[00:41:36] The target species for us would be key in building up that sunflower star cryopreservation bank. In terms of eDNA, expanding and collaborating on monitoring efforts. Cal Academy of Sciences, as well as UCLA are gonna be heavily involved in some of the eDNA monitoring across California. Vibrio pathogen testing is definitely an exciting field where, with our sample collection permit here in Monterey Bay, we may be able to expand our field work in the future.

[00:42:03] And then, we are not certainly satisfied with just putting stars out in cages during this experiment. We can follow the lead of other institutions in Washington and Oregon who have went from caged survivorship trials to experimental small scale releases from a research perspective.

[00:42:22] And so that will be a future step and we’re working through, as with all of the work we do, the necessary regulatory agencies and have had a very strong collaborative relationship with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife to make that happen. We’re also expanding as an organization.

[00:42:37] We’re gonna have five full-time staff come this spring with additional part-time staff and contractors working with us. So our ability to do all of the critical aquaculture to grow stars, as well as research into how to grow stars more efficiently, eDNA research, cryo-preservation studies, and then the field work to actually bring Sunflower stars back is all on the docket for the coming years.

[00:42:58] Michael Hawk: i’m curious, and this may be more speculation, but, if you can speculate now that a causal agent has been identified, what that might enable? I’m not a biologist, so I don’t know if any of this is possible, but, for example, potentially see if there are stars that are naturally resistant in their DNA or is there even such a thing as vaccination?

[00:43:21] Andrew Kim: I think I would like lean more heavily towards the looking for resistance than developing of a vaccine.

[00:43:26] But yeah, that’s the idea. And I think that that’s, an active area, of study. Where we, as Sunflower Star Lab, fit into that area of research is a little bit TBD, but um, yeah, it’s gonna require, years of many numbers of stars to see if there is resistance. What the LD-50 or the lethal dose of Vibrio is for the species. And that all ties in with the cryo work as well, you know, if you do identify re things like resistance, making sure that those genetics are banked away, in the case that they become really important for recovery of the species.

[00:44:01] Michael Hawk: And is the vector understood for how it

[00:44:03] Reuven Bank: That’s still

[00:44:04] Andrew Kim: Yeah, one of those unknowns. Uh,

[00:44:06] Reuven Bank: We know some of the ways that it can spread. We know that just sharing the water with an infected star can lead to the spread of that disease. We know that swapping coelomic fluid between stars can lead to that.

[00:44:18] To what extent other species might also either be carriers or susceptible to this, whether it could come from prey sources and be ingested by the stars. There’s all sorts of novel areas for research there which are best done by laboratories with high biosecurity protocols who can actually handle Vibrio pectenicida in their facility.

[00:44:40] So places like the Hakai Institute are really leading the charge on disease ecology and the spread of seastar wasting as well as at Friday Harbor Labs potentially looking into resistance to wasting. Mm-hmm.

[00:44:51] Michael Hawk: Lots of, uh, threads to follow in the coming months. Is there anything else that you would like to say about the work at the lab or related topics?

[00:45:01] Reuven Bank: We talked about this last time, but just to touch on it briefly here, we do this for Sunflower Stars, but we also do this for kelp because of how important kelp forests are. Our board, our staff have all been ingrained in the kelp forest community, whether it’s researchers or Aquarius or environmental educators who have seen the value and the importance of kelp to the life of all people on the planet. But especially the coastal communities here in Southern California and across our state kelp forests are producing some of the air that we breathe, they’re sequestering some of the carbon in our atmospheres and in our oceans, they’re producing oxygen in near shore marine ecosystems, especially as dissolved oxygen is declining across many areas due to anthropogenic climate change. They also support fisheries, ecotourism. We are connected to kelp every time we breathe, every time we walk on the beach, every time we eat fish, or just want to admire the beauty of an underwater cathedral of forest in places like Monterey and beyond.

[00:46:05] Michael Hawk: , well, it’s an incredible story that you’re part of. I appreciate you thinking of me to share it and looking forward to getting more of this story out to the world. So thank you so much for taking the time today.

[00:46:16] Andrew Kim: Thank you for taking the time.

[00:46:18] Reuven Bank: Appreciate you coming back to the lab, a registered star friend here at Sunflower Star Labroatory.

[00:46:23] Michael Hawk: And one last thing before we go. A huge thank you to Brooks Neely for editing help this week.