#104: Wasting Away: The Battle to Save Sunflower Sea Stars and Kelp Forests with the Sunflower Star Lab – Nature's Archive

Summary

Today we’re going to discuss perhaps the most important 24 armed creature you quite possibly have never heard of before. Each arm has eyes, or more accurately, eyespots on the ends, and they have thousands of tube feet that they closely coordinate to move. It’s a keystone species which used to have populations around 6 billion. And in a matter of a couple of years, about 5 billion of those vanished, melting away, literally turning to goo. Or at least that’s how SCUBA divers and biologists described it. It almost sounds like an alien science fiction story, but I assure you, it’s real.

Maybe you’ve figured out what I’m talking about. And if you listened to my kelp forest interview with Tristin McHugh a few months ago, we briefly mentioned this creature. It’s the Sunflower Sea Star, an amazing creature whose disappearance has caused havoc in marine systems – especially the kelp forests.

So let me set the scene for today’s episode. I traveled 45 minutes from my house in San Jose, California to meet with two folks – Reuven Bank and Andrew Kim. They’re from the inspiring and innovative Sunflower Star Laboratory in Moss Landing, California. Moss Landing is right in the middle of the coast of the world famous Monterey Bay.

It’s a small but bustling town full of marine research institutes, fishers, and ecotourism.

This episode has two parts rolled into one – it’s a sit-down interview, right on the Moss Landing Harbour. And then we go on a mini-field trip – a tour to learn how the Sunflower Star Lab is an important driver in recovering this incredible species.

And as you’ll hear in the recording, we had a lot of…ambiance, from sea lions barking to raucous gulls patrolling the harbor, and the hums and whirrs of pumps and water you’d expect in a large aquaculture facility.

Yes, that’s my way of saying this was a bit of a challenging episode to record and edit. But despite a few rough spots, I think it turned out quite well.

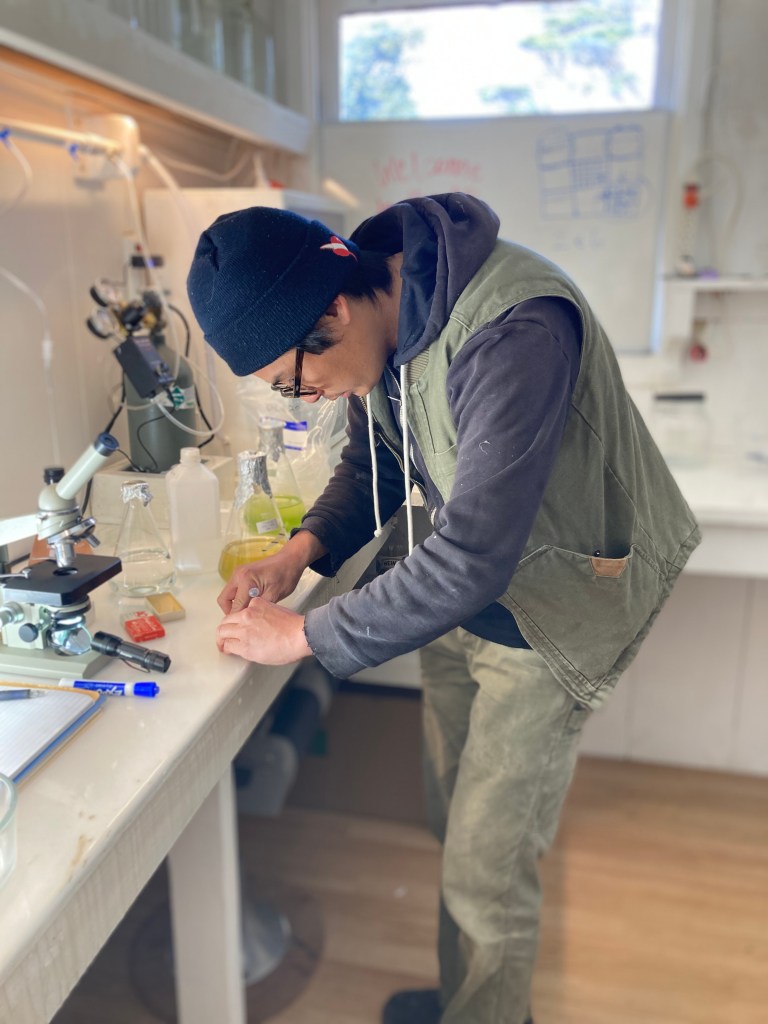

So who are Reuven and Andrew? Reuven is chairman of the board for the Sunflower Star Lab. He’s also an interpretive diving ranger for the National Park Service, though his work at the lab is independent from that. And Andrew is the lead aquaculture research technician at Moss Landing Marine Labs, a member of the Sunflower Star Lab board, offering his expertise on aquaculture to the lab. Oh, and we also had a brief discussion with Vincent Christian while he was working in the lab. As you’ll here, Vincent is the reason why the lab even exists.

Check out the Sunflower Star Lab at sunflowerstarlab.org and on Facebook and Instagram.

Did you have a question that I didn’t ask? Let me know at naturesarchivepodcast@gmail.com, and I’ll try to get an answer!

And did you know Nature’s Archive has a monthly newsletter? I share the latest news from the world of Nature’s Archive, as well as pointers to new naturalist finds that have crossed my radar, like podcasts, books, websites, and more. No spam, and you can unsubscribe at any time.

While you are welcome to listen to my show using the above link, you can help me grow my reach by listening through one of the podcast services (Apple, Spotify, Overcast, etc). And while you’re there, will you please consider subscribing?

Links To Topics Discussed

Pycnopodia Recovery Working Group

Roadmap to Recovery for the Sunflower Sea Star

Links to Related Podcast Episodes

Photos

Credits

The following music was used for this media project:

Music: Spellbound by Brian Holtz Music

License (CC BY 4.0): https://filmmusic.io/standard-license

Artist website: https://brianholtzmusic.com

Transcript (click to view)

Michael Hawk owns copyright in and to all content in transcripts.

You are welcome to share the below transcript (up to 500 words but not more) in media articles (e.g., The New York Times, LA Times, The Guardian), on your personal website, in a non-commercial article or blog post (e.g., Medium), and/or on a personal social media account for non-commercial purposes, provided that you include attribution to “Nature’s Archive Podcast” and link back to the naturesarchive.com URL.

Transcript creation is automated and subject to errors. No warranty of accuracy is implied or provided.

[00:00:00] Michael Hawk: Today we’re going to discuss perhaps the most important 24 armed creature you quite possibly have never even heard of before. Each of those arms has eyes, or more accurately, eye spots on the ends, and they have thousands of tube feet that they closely coordinate in order to move. It’s a keystone species which used to have populations around six billion, And in just a couple of years, about 5 billion of those vanished, melting away, literally turning into goo.

[00:00:26] Or at least that’s how scuba divers and biologists describe it. It almost sounds like an alien science fiction story, but I assure you, it’s real. Maybe you’ve already figured out what I’m talking about.

[00:00:36] If you listened to my kelp forest interview with Tristin McHugh a few months ago, we briefly mentioned this creature.

[00:00:41] All right, I won’t keep you guessing any longer. It’s the Sunflower Sea Star, an amazing creature whose disappearance has caused havoc in marine systems, and especially the kelp forests.

[00:00:51] Let’s hear from Reuven Bank, one of our guests today.

[00:00:53] Reuven Bank: I wanted to get across in this interview how cool sunflower stars are. Not just in terms of how important they are in our ecosystems, but they’re these absolute, you know, Alien looking underwater Roombas, just zooming around as the cheetahs of the subtidal and the inner tidal. where their prey smells them coming and runs off in fear.

[00:01:16] They’re brilliantly colored. They can live for decades. It’s a life that seems wholly different to our own, the way that they’re living in the ocean. And yet, because of their importance to kelp forest ecosystems, we are inexorably connected to sunflower stars, despite how different they may be from us.

[00:01:34]

[00:01:34] Michael Hawk: So let me set the scene for today’s episode. I traveled 45 minutes from my house in San Jose, California.

[00:01:41] to meet with two folks, Reuven Bank and Andrew Kim. They’re from the inspiring and innovative Sunflower Star Laboratory in Moss Landing, California. If you don’t know Moss Landing, it’s right in the middle of the coast of the world famous Monterey Bay.

[00:01:57] It’s a small bustling town full of marine research institutes, fishers, and ecotourism. This episode has two parts rolled into one. It’s a sit down interview right on the Moss Landing Harbor, and then we go on a mini field trip, a tour to learn how the Sunflower Star Lab is an important driver in recovering this incredible species.

[00:02:15] And as you’ll hear in the recording, we had a lot of, uh, ambiance, I would say, from sea lions barking to raucous gulls patrolling the harbor, and the hums and whirs of pump and water movement that you’d expect in a large aquaculture facility. Yes, that’s sort of my way of saying that this was a bit challenging to record and edit, but despite a few rough spots audio wise, I think it turned out quite well.

[00:02:39] So who are Reuven and Andrew? Reuven is the chairman of the board for the Sunflower Star Lab. He’s also an interpretive diving ranger for the National Park Service, though his work at the lab is independent from that. And Andrew is the lead aquaculture research technician at Moss Landing Marine Labs, a member of the Sunflower Star Lab board, and he’s offering his expertise on aquaculture to the lab.

[00:03:03] Oh, and we also had a brief discussion with Vincent Christian. While he was working in the lab. And as you’ll hear, Vincent is really the reason why this lab even exists. So check out the Sunflower Star Lab at sunflowerstarlab. org and on Facebook and Instagram at Sunflower Star Lab.

[00:03:20] The tour was very visual. So be sure to check out the show notes on naturesarchive. com for photos of our “star” sea star of the day. That was Hannibal, as well as some various elements of the lab. So without further delay, let’s learn about the Sunflower Star and what caused it to dissolve before our very eyes and what this dedicated team is doing about it.

[00:03:41] Can you tell me about where we’re at right now and how you came to locate? here.

[00:03:48] Andrew Kim: Yeah, well, we’re at the Moss Landing Boat Works just uh, across the street from MBARI, the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research

[00:03:56] Michael Hawk: I saw the Rachel Carson there as I drove in.

[00:03:59] Andrew Kim: Yeah, down the street from, Moss Landing Marine Labs as well. And yeah, we’ve been lucky to have this space donated to us by the owner of this lot, who is a passionate conservationist,

[00:04:15] Reuven Bank: yeah, it’s been a very fortuitous, real estate spot

[00:04:18] So Andrew, how did you get interested in nature and marine systems in the first place?

[00:04:25] Andrew Kim: I grew up in Los Angeles, around Koreatown. And, as close as you are in LA to the ocean, I didn’t really spend much time thinking about it. Didn’t really, have a family that, Did too many outdoorsy activities growing up and Was not particularly like a good student in STEM and sciences I had a Revelation, when I got to college, I went to UC Santa Cruz, I was an undeclared, major, and kind of lost, flipping through the course catalog, and came upon the description for, kelp forest ecology, which was a class where you would, design, observational studies, dive in the kelp forests, I had a lot of, doubt about my ability to get through, the sciences and things like that.

[00:05:13] In general, I, forced myself to get through all the prerequisites and got myself to the point where I was diving, and I literally just, got in the water as much as I could and, fell in love with the kelp forest ecosystem. It’s hard not to when you’ve been out there on, a clear day and you’re swimming around under the canopy.

[00:05:32] It’s just an unbelievable, indescribable feeling, so for the last, about 15 years I’ve been working with, in and around, the kelp forest ecosystem. so out of college I,worked at the Monterey Abalone Company, which is an in ocean abalone farm here in town.

[00:05:52] and I worked there for many years as a manager, and it’s a business that kind of lives and breathes with the kelp. And it was at that point that I, you know, and as a part of my job, I was diving very frequently as well. And, yeah, I watched the sunflowers melt away. I watched the urchins crawl out of the cracks.

[00:06:08] And I saw tons of kelp disappear. now I’m the lead aquaculture research technician here at Moss Landing Marine Labs and I get to be involved in all sorts of aquacultural related, projects.

[00:06:22] Michael Hawk: And, Reuven?

[00:06:22] this is one piece of a larger career you’ve had in marine systems.

[00:06:26] What led you to, cultivate this interest?

[00:06:29] Reuven Bank: I’d say this particular interest in Sunflower Star Recovery started when I moved to the West Coast. I grew up in Baltimore, Maryland. I got outside quite a lot, so I knew that I wanted to work for, who is now my current employer, of the National Park Service since I was probably in high school or college.

[00:06:47] But, I didn’t know a ton about kelp forests and kelp forest environments, really anything that happened on the West Coast or in California. But when I moved to the West Coast in 2021, the first dive I ever did was at Monastery Beach, which is a legendary local site with this cathedral of kelp all around you and absolutely gorgeous marine environment and I pretty quickly Fell in love with our kelp forest ecosystems here, and also pretty quickly started learning about the threats that they’re facing, especially regarding, the loss of keystone predators such as sunflower stars.

[00:07:29] So, like a lot of our, managing staff here at the laboratory, I found out about this general idea from when our now lab manager Vince Christian put a Facebook post out in a local, Monterey Bay scuba divers page about his potential interest in his grand visions of creating an aquaculture laboratory for restoring sunflower stars.

[00:07:52] And he was recruiting people to join and co found this organization and achieve that vision. So we went from the summer of 2021, an idea being floated out in a Facebook group, to December of 2021, an oddly well suited collection of people. Concerned community members with experience in everything from aquaculture to environmental education to non profit management and even legal policy assembled together, pretty quickly to create this organization and, find ourselves where we are now.

[00:08:25] So, in, you know, from a very myopic view, it started just with a Facebook post from when, we were trying to galvanize support for this organization.

[00:08:33] Michael Hawk: I always feel somewhat heartened by that because for all the negatives and dislikes I have for social media, occasionally these stories crop up where. Social media works for good.

[00:08:43] Reuven Bank: And a lot of folks hear about our laboratory from our social media, whether it’s donors, volunteers, concerned community members, they find us and the content that we share. about the

[00:08:54] Andrew Kim: I had the old school Vince interaction He was just like putzing around Moss landing trying to talk to anyone He could about Picnipodia and I just happened to be around and this was like still during like lockdown COVID so like students weren’t around people weren’t around and I just you know happened to be like the one person around I

[00:09:14] Michael Hawk: Hey you, I want to talk to you about this idea.

[00:09:17] Reuven Bank: Yeah, and if you were going to hay you anybody in the general area about this, Andrew’s a pretty good person to, uh, accost

[00:09:25] Andrew Kim: , Okay, here we are, Sunflower Star Laboratory. What is a sunflower star?

[00:09:31] Sunflower star is a large predatory, uh, sea star in the phylum of, Echinodermata, which is a group of marine predators. invertebrates that you can find around the world, includes things like sea urchins, sea cucumbers, crinoids, that sort of thing. Very diverse, very prolific, very ancient,

[00:09:57] Reuven Bank: Yeah, our last common ancestor with echinoderms, you have to go back over 500 million years to find, species that we may have both evolved with. So, compared to us, they’re almost alien in many of their, functions and anatomy and structure. And sunflower stars in particular are these really incredible They’re one of the largest sea stars in the world.

[00:10:18] they can span over a meter across and have, as adults, anywhere from 18 to 24 arms and brilliant coloration, which can be anywhere from almost whitish to pink to more commonly orange and purple and sometimes a mixture of the two. So they’re these brilliantly colored sea stars which were once found across a historic range from Alaska all the way down into Baja, California.

[00:10:43] Michael Hawk: you said 18 to 24 arms, potentially. Is 24, like, does it seem to be a hard limit, or is it possible that there could be sea stars out there?

[00:10:53] Yeah, which is pretty, amazing, because I know, I didn’t grow up near the ocean, so a lot of what I knew about, starfish and, other ocean creatures was whatever I happened to see on TV, sometimes they even be cartoons, and usually the sea stars you see on cartoons are these little, five armed, pink.

[00:11:13] Reuven Bank: More than once I’ve heard people do impressions Spongebob when talking to our outreach team.

[00:11:18] Michael Hawk: somehow I didn’t even think of that. I don’t know why that seems obvious now.

[00:11:21] Reuven Bank: I think Patrick’s probably a bat star, wouldn’t you think?

[00:11:23] Andrew Kim:

[00:11:23] I like to think that Patrick’s a, short spined star. Yeah, Pisaster brevis spinus,

[00:11:29] Reuven Bank: Coloration matches for

[00:11:31] Andrew Kim: sea star. Yeah, yeah. But, you know, who knows.

[00:11:35] Reuven Bank: edited out the spines in

[00:11:37] Michael Hawk: From the little bit I know about these creatures, they start off tiny little tiny. And, uh, and obviously get up to a meter from what you just said.

[00:11:46] Andrew Kim: So can you walk me through, their life cycle? Yeah, they start small. I mean, don’t we all?

[00:11:52] Reuven Bank: so yeah, Sunflower Sea Stars, as Reuven mentioned, had this great historic range. They, are broadcast spawners, which, means that sperm and eggs are ejected into the water and kind of the motion of the ocean essentially does the fertilization.

[00:12:09] Michael Hawk: I was thinking a little bit about analogies for this, and the first thing I thought of is like, wind pollination and plants, but that’s a little bit different, too, because there’s, there’s a destination tree that, you know, that pollen needs to get to, a destination, you know, there’s a destination it has to get to, where here the ocean is kind bringing them together.

[00:12:28] Andrew Kim: yeah, and the ocean’s just, you know, it’s just a big ol soup, right? there’s all kinds of things floating around, constantly. I mean, it’s

[00:12:38] Reuven Bank: now that you said that.

[00:12:39] Michael Hawk: same

[00:12:39] Andrew Kim: Certain times of year or potentially the presence of just sperm or eggs of a similar species might elicit this response, this spawning response.

[00:12:51] And Pycnopodia eggs are really heavy and so the females will kind of, when the time is right, or maybe they are sensing sperm or there’s a tidal trigger or some other environmental light or temperature signal that triggers that. induces the spawning, um, and the eggs kind of trickle down and the sperm,

[00:13:13] comes floating by and there’s a bit of magic there, right?

[00:13:17] Like, to what degree is fertilization, what is the general population density required to have successful, fertilization? Those are big questions. Required for just general outplanting and restoration efforts as well that need to be answered that are unknowns, but

[00:13:36] Reuven Bank: Yeah, I mean, sunflower stars are really uninvolved parents compared to us. Uh, they’re not dropping their kids off at baseball practice. They’re ejecting millions of eggs and sperm out into the water column, which are fertilizing outside of themselves. And they have a couple of really distinct life phases, once they’ve had their eggs fertilized out in the ocean.

[00:13:56] Because once they’re fertilized, they’ll turn into larvae, and can spend upwards of a month floating out in the open ocean.

[00:14:03] And then it can be multiple months after that. Which is why the genetic profiles across the historic range is pretty well mixed for such of a long span of thousands of miles.

[00:14:13] It’s because if you’ve ever seen, like buoy markers that are listed as just GPS data that track their movements according to ocean currents. Over the same timeline, if you have floating larvae of Pycnopodia, they can really move up and down the coast.

[00:14:28] Andrew Kim: Yeah, so they’re floating around, possibly not floating very far,

[00:14:31] Who knows?

[00:14:32] There’s another just like mystery there, but the potential for dispersal is very large Settle out very far from your parents essentially the larvae are out there growing, doing their thing, and when they reach a certain size, and they’ve developed all the structures necessary to settle out, once they encounter suitable substrate or habitat or cue, they can undergo metamorphosis.

[00:15:05] And at that point, this little two millimeter ish plus.

[00:15:11] Reuven Bank:

[00:15:11] Andrew Kim: larvae

[00:15:11] Larvae will metamorphose into, just a little half a millimeter sea star that emerges from, this little spaceship of a larva. something kind of interesting that I’ve been able to do up at the lab

[00:15:25] is we have these larvae that settled, at 27 days, which is not known from the literature. and then I still have six months on, a couple of beakers of larvae. And so it’s less of this, like, I’m this many days old, so I must be ready to settle.

[00:15:45] It’s

[00:15:45] Michael Hawk: Some other amalgamation

[00:15:47] Andrew Kim: yeah, like, am I ready? Do I have the structures? Have I built, the necessary things to survive and undergo metamorphosis, which is this very dramatic. Right,

[00:16:00] Michael Hawk: then about kind of like the bounds of normal, quote unquote normal, because it’s in a lab, but, you know. Possibilities, you know, with this organism.

[00:16:09] Andrew Kim: Yeah, exactly. And so one of the things that we’ve been able to figure out is that they are extremely discerning when it comes to, settlement. They would rather starve and wait, than to just settle in the absence of, a good, strong cue. Which, tends to be things like coral and algae.

[00:16:29] are a pretty traditional and well known, inducer of settlement across marine organisms, including, seaweeds. and coralline seem to work pretty well for the pycnopodia as well.

[00:16:43] Michael Hawk: How long, would a healthy, mature adult live? How long does it take to get to, like, maturity? Is there a clear boundary?

[00:16:50] Andrew Kim: Yeah, I mean, and that’s one of those things too, right? Like, it’s not necessarily age. It’s more of, like, size and, and diet and, and energy. and so, but generally I think Jason has seen that, like, they can start to produce, gametes at to three years.

[00:17:10] Reuven Bank: and then how long can they live?

[00:17:12] The estimates are in the multi decade level. We’ve seen some 60 years old. They’re incredibly long lived creatures. And there’s some which are extremely rare. in flow through systems in aquariums in California that have survived because they were taken in before sea star wasting syndrome in 2013 2014.

[00:17:34] So there are numerous in California that are over a decade old, but it’s thought to be many decades in terms of their total lifespan.

[00:17:43] Andrew Kim: Yeah, but it could be one of those things, I mean, and as it is for lots of marine invertebrates, like, does anyone know? Who knows? They could be, you know, I mean, like a red sea urchin could live, you know, hundreds of years. but, with a sea urchin, they have this test, they have this shell that you can go back and kind of use to age.

[00:18:00] a sunflower sea star is actually in contrast They are very soft bodied and so there’s not really a lot of stuff left behind for you to go back and look at.

[00:18:10] Reuven Bank: The texture of their exterior,

[00:18:13] But if you look at macro photography or really close ups of the exterior of sunflower stars, it almost looks like fleece and fuzziness between, the various, parts of the organism that you can see there. So like Andrew was saying, it’s very different in texture if you touch a sunflower star versus a harder sea star like a bat star.

[00:18:31] Michael Hawk: often there’s a correlation, and I think there’s a term for whoever, documented the correlation of the larger the animal or the longer lived. Actually, maybe it’s a better example. The longer lived the animal, typically the lower reproductive rate they have. It sounds like in Marine systems that doesn’t necessarily hold as strongly.

[00:18:52] Reuven Bank: Yeah. and that’s, that correlation is also with parental investment, which also doesn’t correlate as strongly here. So there’s K selected species, which usually have really long lives on land and are very invested in their few offspring that they do have, versus R selected species, which have a lot of offspring, frequently, but don’t necessarily put a ton of investment into each individual one.

[00:19:18] And so the lifespan of sunflower stars in particular doesn’t quite fit that general trend.

[00:19:23] Michael Hawk: can you tell me a little bit about their body plan and how that relates to their making their way through their environment? Like we talked about the arms, but I know there’s more, For what we’re used to on land, you know, they’re very different creatures.

[00:19:38] Andrew Kim: Right. just imagine, A a big sea star, as best as you can with lots of arms.

[00:19:43] So, yeah, I mean so, yeah.

[00:19:45] Michael Hawk: Patrick.

[00:19:46] Andrew Kim: Imagine Patrick with a bunch of arms and like tens of thousands of tube feet that are working in this, water vascular system. And so, what I mean by that is that there’s, essentially they have like a hydraulic system that they use to, pressurize, their tube feet and, somehow coordinate the movement of these tens of thousands of tube feet to pull themselves in one direction or another.

[00:20:11] And they can move extremely fast, like over a meter a minute, in these adults. as they are literally hunting and chasing and pouncing on prey items. they’ve got a soft body, so their typical method of feeding is to just engulf their prey whole. in the case of, the sea urchins, they take in this pincushion and spit out just, a pile of spines and a perfectly clean, empty test or shell.

[00:20:40] Reuven Bank: And they have internal and external components to their stomach system, where they’ll actually spit out part of their stomach contents and start digesting their prey outside of their body. if the prey is small enough compared to their size, like Andrew said, they’ve got, the ability to kind of widen their mouth opening and take the entire whole urchin or entire whole snail into their body and spit out the undigestible portion.

[00:21:05] Michael Hawk: Is that, a mouth? Where the stomach system comes out? Is that kind of centrally located on the star?

[00:21:11] Andrew Kim: So there is like a top side and a bottom side, of the sea star. The top side would be where the madriporite is, which is the little calcified structure that sucks in, seawater to pressurize the water vascular system, as well as the anus, which is kind of centrally located on the, on the disc. and then just right, essentially on the opposite side of the anus is this large mouth, which can,

[00:21:35] yeah, like.

[00:21:36] Slightly avert, not avert in the same way that some other star species might, like ochre stars that are really just pushing their stomach into nooks and crannies and digesting prey items outside of their bodies, which is kind of a wild thing, right?

[00:21:51] pykno,

[00:21:52] they, they’ve got all these arms and You know, sea stars are known for their regenerative capabilities, and pycnos are also, historically have been known for that, and they,

[00:22:06] you know, if there’s a crab or something that might come around and, is looking for a treat, a defense mechanism, that the pycno might, exhibit is just to drop an arm, and move on.

[00:22:19] Reuven Bank: Pycnopodia have very few identified predators. Down here, where we are, there are documented cases of an otter taking an arm or two. And then up in the more northern aspects of their former range, like Alaska, king crab are a known predator of sunflower stars. But usually a predatory event will involve running off with an arm, rather than the entire pycnopodia.

[00:22:42] Andrew touched on the many tube feet that the Sunflower Stars have, and the term for those tube feet is podia, so their genus name of Pycnopodia is basically many tube feet, because they have those 15, 000 tube feet. if we’re picturing a Sunflower Star, Sunflower is a really good common name for it, because you’ve got almost that central flower area with the many petals, like arms, going off in any direction.

[00:23:05] So on one side is this, like, soft fleece covered flower. You’ve got all of those podia wiggling around and directing food towards their mouth.

[00:23:15] Michael Hawk: I’m glad you went there because, that had been a lingering thought. I was like, I can’t quite see the sunflower, but when you describe it like that, yeah, it makes sense. I guess another thing that stands out to me as, as being very different is, they don’t have a centralized brain and centralized nervous system, right?

[00:23:31] Like, what’s going on there?

[00:23:33] Andrew Kim: Well,

[00:23:34] there are lots of ways of being, right?

[00:23:36] They have, eyespots, like light detecting, cluster of cells at the tips of each of their arms, as well as lots of, nerve cells that help them move around, hunt, and they are very effective hunters, Yeah, so they have, you know, it may not be a centralized nervous system the way that we think about it, but it’s definitely an effective, manipulation and processing somehow of,

[00:24:04] Michael Hawk: of a mystery how they make sense of the world and make decisions and

[00:24:09] Andrew Kim: Right, yeah. I mean it’s a lot of little tiny extremities to move around.

[00:24:15] Reuven Bank: all at once, yeah.

[00:24:16] Andrew Kim: sometimes

[00:24:16] when you’re looking at a pycno, it feels like, you’re watching it and it can’t, make a decision on, which direction it wants to go. And you can see, different parts of the star kind of, reaching in different directions.

[00:24:25] Michael Hawk: But, eventually, the message gets across and they’re able to get to where they’re going. Reminds me a little bit of, when I had, Sy Montgomery, talking about, octopuses on the podcast. And, there was a kind of a similar discussion there, how individual arms sometimes seem to have their own decision making process

[00:24:43] Reuven Bank: Yeah, Yeah, And that’s almost far in the other direction of having that almost internal, system within each arm. So it’s almost like you have too many quasi brains as opposed to not enough.

[00:24:55] Michael Hawk: so let’s get into the threats a little bit, which I guess is, why you’re here. You alluded to sea star wasting syndrome, and, pre 2013. so let’s just go back to, say, 2012 or 2011 What was the status of these sea stars back in that era?

[00:25:11] Reuven Bank: Yeah, so sunflower stars were widely dispersed from all the way up in Alaska down into Baja, California. There were estimated six billion or more individual sunflower stars across that historic range. sunflower stars are found in a lot of different coastal environments, and they eat a lot of different things.

[00:25:31] They can be found in sandy substrates, seagrass, the rocky intertidal, or sub tidal rocky areas where kelp forests and other ecosystems will grow. they’ll also eat a bunch of different prey. They can dig prey out from underneath the sandy sediment below them. They can chase them through the, kelp forest environment.

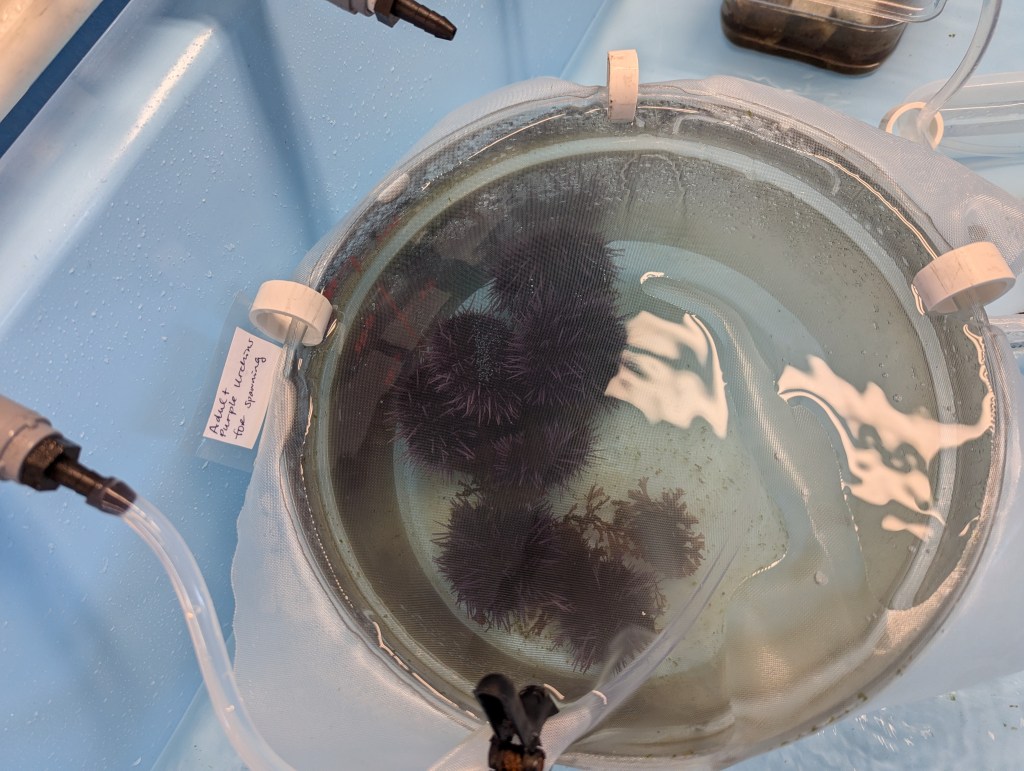

[00:25:51] They can hunt in tide pools in the rocky intertidal. but they had a profound impact. on the ecosystem around them, through the different prey that they ate. Because if we go back to that 2011 2012 period, here, especially in northern California, there were a few historic predators of a species called the purple urchin, which is a fellow echinoderm, which is a grazer on kelp, especially drift kelp, if we’re talking about before sea star wasting syndrome.

[00:26:20] And sunflower stars ate a bunch of different things and lived in a bunch of different areas, but they were really important for their ability to control purple urchin populations, both by eating them as a predator and also by scaring them. Because they create, to quote Dr. Sarah Graven at Oregon State University, a landscape of fear in the general environment around them, where up to 16 feet in every direction, they create a halo effect, where not just purple urchins but other prey species such as marine snails can smell them coming and elicit a fear response from this predator.

[00:26:53] So sunflower stars, back before sea star wasting syndrome, had a really important role as a keystone predator by eating and also scaring urchins in the environment and helping to keep the kelp forest healthy. Almost analogous to wolves in a park like Yellowstone keeping herbivores in check.

[00:27:09] Andrew Kim: And just from like the perspective of a diver, someone who had been diving here, actively pre wasting, they were an extremely conspicuous and I would say fairly abundant,

[00:27:20] organism. And you’d see them, on every dive and you almost kind of took them for granted.

[00:27:25] Reuven Bank: That’s something our laboratory manager, Vince Christian, mentions a lot, is he never really appreciated them when they were here, because they were all over the place, and we talked to a lot of underwater photographers to see if they have any photos that we might be able to use for the lab, and by and large they’re like, no, I never took pictures of those, they were everywhere.

[00:27:43] Michael Hawk: What was the first hint that something was going wrong with the populations?

[00:27:49] Andrew Kim: so I think what was really shocking is that the sea star wasting appeared, seemingly out of nowhere, and it wasn’t like a trickle, it was just open the floodgates and every star was melting away,

[00:28:04] Michael Hawk: as a diver, you were seeing

[00:28:05] Andrew Kim: Yes, yeah, and it’s not like it was something that you would see an individual star struggling with over time.

[00:28:12] It was literally like, they would melt away in days. that was the most alarming thing, I think, the sea star wasting event was almost kind of like a blip where this thing came through and totally, wreaked havoc on Pycnopodia in particular. They were the hardest hit and the quickest to go.

[00:28:32] it really just came through gutted the population.

[00:28:36] Reuven Bank: was very sudden and it was also extremely pervasive. Seastar wasting syndrome is one of the largest marine epidemics on record. It impacted over 20 different species of sea star. And like Andrew was saying, it was almost overnight where you had the symptoms of wasting start to occur. Because wasting almost describes a collection of symptoms.

[00:28:57] Almost like sepsis in humans, where you have ending up in total body failure on behalf of the sea star. So it would start with symptoms such as, The star is almost looking deflated and arms beginning to twist, to soon arms dropping off and eventually the entire star turning into a giant mushy pile of goo.

[00:29:18] Andrew Kim: And I think when people were observing this sort of thing happen, because, you know, sea star wasting is not a necessarily new phenomenon. It’s like you say, it’s not a very, like, clearly defined, disease. it’s a set of symptoms, and those symptoms had been observed in pycnopodia and in other sea star species for decades.

[00:29:36] But it was something about this blip of time that was just, it was catastrophic.

[00:29:41] Reuven Bank: there have been other large outbreaks of wasting amongst sea star populations, including sunflower stars in the past. In the early 1990s there was a pretty pervasive, event, but still dwarfed by what happened in 2013, 2014. And this outbreak of sea star wasting syndrome is directly correlated to a multi year period, often referred to as the blob, where there were elevated sea surface temperatures for numerous years.

[00:30:07] So for a couple of years, the ocean got abnormally hot, and we had this prevalence of what was likely a disease spread amongst sea star populations, particularly hitting sunflower stars. Because their former range was Alaska down to Baja, and pretty soon, Sunflower Stars became functionally extinct on the southern part of their range.

[00:30:28] Here in California, we have a handful of sightings, maybe in northern California every year, but they’re functionally extinct because they can’t contribute the same role in the ecosystem and their function as keystone predators as they previously did. So we went from You would see a sunflower star on just about every dive to, we haven’t had a confirmed sighting of a sunflower star south of the Bay Area since 2018.

[00:30:53] Andrew Kim: Yeah, and I think, just to add on that, like, when the stars were wasting away, it just, it was sudden, it was dramatic. Everyone knew that that was a problem, but nobody knew the degree to which it would, affect the ecosystem. and so the strength of this keystone species, the degree of, impact that it had, was really,

[00:31:15] We just lacked the baseline, really.

[00:31:17] Reuven Bank: can see that in the research into sunflower stars too, about not really poking them too much and studying as many aspects of the star as you might do with a now critically endangered species because the community. took them for granted. People knew about their role of eating urchins, but we have found out, especially since they have disappeared, just how important they are as keystone predators.

[00:31:40] In the locations where you still have some of the population further north, do you see the wasting syndrome still working its way through those populations?

[00:31:50] Reuven Bank: We see wasting in California still, as well, with the species that are still functionally extant in our state. So, wasting is still a problem. Uh, existent here in California as well as farther north in populations where there are still sea stars, sunflower sea stars. Washington state still has about 7 percent of its historic sunflower star population.

[00:32:11] Different parts of Alaska can have anywhere up to like 40 and some places even 60 percent of their historic population as of 2021. But wasting is still present in our marine ecosystems because it was always present then. And since the specific pathogen or, combination of pathogens, whatever might be driving sea star wasting outbreak 2013 2014, hasn’t been, identified, it’s hard to say whether any individual wasting event that occurs in the ocean is tied to the exact same cause as this outbreak that occurred 10 years ago.

[00:32:45] Because if you don’t know the disease that’s causing these symptoms, it’s hard to say that that disease is now still present.

[00:32:52] Michael Hawk: . So this 2013 outbreak, beyond the sunflower sea star, what else was affected?

[00:32:59] Reuven Bank: Over 20 different species of sea star. So many of the common ones, where if you go tide pooling in California, they might be familiar to you. bat stars, giant spine stars, ochre stars were all hit hard by this, outbreak. But we’re starting to see signs of recovery in California of many of those other species.

[00:33:17] And they didn’t reach the level of functional extinction that occurred for sunflower stars.

[00:33:21] Michael Hawk: So one of the reasons why We connected was, because I did a recent episode with Tristin McHugh talking about kelp systems and how kelp systems had really been impacted and

[00:33:31] as I learned in that discussion, the sunflower sea stars play an integral role in the kelp systems, as well. So, whether it’s kelp or other marine systems, how has the decline and loss Yeah, The major causes in their recent decline has been the absence of sunflower stars, these keystone predators. Because of their ability to both eat purple urchins and scare purple urchins, sunflower stars had this incredible role in keeping their populations in check and keeping their behavior in check in healthy kelp forest ecosystems.

[00:34:18] Reuven Bank: And when almost overnight, as Andrew described, you have over 5 billion sunflower stars across the historic range turn into goo, We are now missing this Keystone Predator, which is compounded by the fact that we are also missing a previous Keystone Predator the Southern Sea Otter across much of California outside of Pockets and Moss Landing, Monterey, and Morro Bay.

[00:34:40] They’re mostly absent.. And the purple urchin populations almost directly after the disappearance of sunflower stars. exploded and their behavior changed from passive grazers on drift kelp to more active raising of kelp forests.

[00:34:54] So because of that, disappearance of the sunflower star, we had in part 96 percent of northern California’s kelp forests disappear in the last decade. That’s not all entirely due to the loss of the sunflower star.

[00:35:10] I’m thinking about, you know, again, the classic ecology 101 thing that you know, when a prey species increases dramatically because a predator has declined, eventually the prey species is going to consume whatever resources in its environment that causes it to crash or the predator comes back.

[00:35:28] Michael Hawk: In this case, the predators are not coming back anytime soon. but what happens to the urchins? are they going to reach a point where they have consumed all of the resources and then they crash?

[00:35:42] Reuven Bank: Urchins can live for years in a starving state. So across, especially northern California, we’re seeing these barrens form, where they basically have munched down all of the brown macroalgae, like the bullkelp forests that were once there. And so they’re subsisting on far less of that foundational species than used to be out there.

[00:36:04] And so if you go into an urchin barren and you crack open one of those urchins, inside they’re basically shriveled husks of their former selves, where the gonads are incredibly small and, you could crack open an entire field of them and maybe not have enough uni for a big dinner. so we’re seeing the, the urchins, dealing with the situation of being in the barren that they in part created by eating through that kelp.

[00:36:30] Andrew Kim: Yeah, but it is, it does appear to be this stable state. I mean, there are urchin barrens that have been set up and existing for decades, in other places. and yeah, they’re able to just tap into this lower metabolic state where they need very few, inputs. And then, you know, I mean, we were talking about cannibalism, but there’s cannibalism

[00:36:51]

[00:36:51] Reuven Bank: Barrens, both urchin barrens or especially farther south, brittle star barrens, are a natural component of marine ecosystems. They can be a very stable state. And if you look at Longer term ecological monitoring in California. They’ll be present at certain sites, turn into kelp forests, and maybe in other places you’ll turn into barrens.

[00:37:11] But it was the scale and the speed at which we had 96 percent of Northern California’s kelp forests just disappear, in many cases turning into those urchin barrens, which is what was so alarming.

[00:37:22] And this decline in our kelp populations here in California, in part due to the loss of one of the only major predators of purple urchins that was left in the marine ecosystems, has tremendous cascading impacts both on the ecosystem around it, as well as on all of us, whether we are living in California or not.

[00:37:46] Kelp forests are these incredibly environment marine ecosystems of macro algae that form forests underwater. In canopy forming species like bull kelp and giant kelp. They harbor over a thousand different marine organisms who utilize the foundation. They provide both providing food and shelter for the many species of fish, invertebrates, algae and others.

[00:38:11] They also help reduce coastal erosion. they can mitigate wave action and, uh, soften the impacts of coastal erosion, which is a particularly salient issue now, as our sea levels continue to rise. They also sequester carbon and produce oxygen and are pretty vitally important ecosystems for just about everybody, both in our country and our world.

[00:38:35] Even if you’ve never set Flipper into a kelp forest, you have benefited from the ecosystem services of kelp.

[00:38:43] Michael Hawk: So I think I have a decent idea of what the impact now between, you know, the conversation I had with Tristin and you folks on the kelp systems. So tell me now, this lab here, what is your vision? Like, what do you hope to accomplish with the work that you’re doing? And then we can work backwards from that as to how you’re doing it.

[00:39:03] Reuven Bank: Sunflower Star Laboratory was formed by a group of concerned local community members who were watching our kelp. In some cases, literally before our eyes, there are particular dive sites here in the Monterey area, which are being encroached upon by urchin barrens, and you see the kelp forest shrink every year.

[00:39:24] And we were inspired to take action, catalyzed initially by, who is now our lab manager, Vince Christian. our board co founded the organization in December of 2021 with the goal of, Being able to restore and recover sunflower star populations in order to combat the unfolding kelp crisis that’s happening here in California and beyond.

[00:39:47] Michael Hawk: So your goal then is to help restore this population. Now how are you doing it?

[00:39:52] Reuven Bank:

[00:39:52] Michael Hawk: what’s happening behind these walls here?

[00:39:54] Reuven Bank: Yeah. So behind these walls, we are actively growing and culturing juvenile sunflower stars, from their current state towards adulthood. We are also growing. species of microalgae, which we can use to feed larval sea stars as well as larval stages of other organisms like purple urchins that we are also growing in order to feed our sea stars.

[00:40:20] So we’re trying to almost recreate an ocean ecosystem within our laboratory in order to benefit the conservation of this species for working towards their eventual restoration in the wild.

[00:40:34] Michael Hawk: So you devote a lot of space and time and effort into those foundational pieces, to support the sea stars.

[00:40:40] Andrew Kim: Right. And I

[00:40:41] think, yeah, the Sunflower Star Lab now also has this really important role of efforts across, the Creator Working Group, the Pycnopodia Recovery Working Group, all along the West Coast and as kind of this community, beacon for education and outreach, around this matter.

[00:40:59] And, I think we’re looking forward to contributing to the research and understanding of everything that goes into the restoration effort. It’s not like we’re out here just like that. A group of cowboys trying to put, Sunflower Stars out, willy nilly. Like, it’s going to require, multi state, and even just within state, massive coordination.

[00:41:19] Michael Hawk: So not just the aquaculture side, but then when you get to the stage where you’re ready to start reintroducing the stars back into their environment, that’s not something like you just put them all out there and see what happens.

[00:41:30] Right. It’s a process.

[00:41:31] Reuven Bank: will take an incredible amount of coordination, both amongst researchers to determine what protocols outplanning, but also with relevant government organizations for permitting, such as California Department of Fish and Wildlife, other state regulators as well. And what’s happening inside of the laboratory is one facet of the work that we do, but Sunflower Star Laboratory is taking a holistic approach to sunflower star conservation, where we have our Conservation Aquaculture Program Manager, Ashley, who works between other members of the Pycnopodia Recovery Working Group to help the and general conservation efforts of sunflower stars amongst partners.

[00:42:14] We also have a conservation geneticist on our staff, Dr. Loren Schiebelhut, who is working towards better understanding the genetics of sunflower stars as well as other species of sea stars to potentially better aid in their restoration efforts. And we also have a significant component of our lab devoted to outreach.

[00:42:32] We have a team of outreach volunteers as well as board members who will do everything from on site outreach at our lab with passers by. But also going out into the community, speaking at community events, doing trips to local schools, and talking to everyone from elementary school to high schoolers.

[00:42:50] So we’re trying to really further the community based aspect of our founding with the work that we do here.

[00:42:57] saw some of the progress that you’ve already made. in this, and there’s a number of, two to three centimeter, sea stars in there. so tell me, like, when you started this endeavor in 2021, did you expect to be this far along in 2024 how are you feeling with the progress that you’ve made?

[00:43:16] Reuven Bank: We have developed really rapidly. This is, I would describe us as being a little ahead of schedule. Which is very exciting and a little bit scary. But, we, there was a galvanizing of community support around our organization. Everything from the volunteer efforts to donations to help keep the lab running.

[00:43:34] the Monterey community and the Monterey Peninsula and Bay Area as a whole really helped us. Understood the impact of losing Sunflower Stars and rallied around our organization to where we are probably over a year ahead of schedule of our initial development plan that we outlined for our organization.

[00:43:53] We’ve cleared a number of major hurdles, we still have others still to come, but we’re moving pretty rapidly for a species as important and endangered as the Sunflower Star.

[00:44:06] Andrew Kim: Which, you know, I think in retrospect, yeah, like that’s great, but it makes sense, because it is like a crisis situation, you know, and so I think that’s really, helped move things, much more rapidly. which is great, and we’re luckily prepared for that growth, and, are happy to be on schedule, or ahead, and prepared for, prepared to be behind as

[00:44:29] Reuven Bank: Yeah, and to put it into context, one of the other major, marine conservation efforts and aquaculture specific to marine invertebrates in the state is the White Abalone Project, trying to save that critically endangered species. That species was listed on the Endangered Species Act around the year 2000, and the first outplanting of White Abalone occurred in 2019.

[00:44:49] So, on a timeline scale, sunflower stars haven’t even been officially listed on the Endangered Species Act yet, and we’re already multiple steps away. towards restoration. Certainly not all of the way, but we are actively growing juvenile sunflower stars in this lab.

[00:45:04] Michael Hawk: How many do you have now that you would classify at the juvenile stage?

[00:45:08] Reuven Bank: Dozens.

[00:45:09] Michael Hawk: Between 30 and 40. I think it’s like 36 actually, As I understand it from the plan that you have on your website, you know, you’re in this process of scaling up and learning, you don’t jump in and suddenly have hundreds or thousands, you start somewhere. So what do you see as the next step in terms of scaling up the operation,

[00:45:32] Andrew Kim: yeah,

[00:45:33] Reuven Bank: Roadmap to Recovery is a very helpful document for determining that.

[00:45:38] Andrew Kim: I mean, I could, I’ll speak to the general answer a little bit first, but it’s good to tie in the roadmap to recovery, because I think that. You know, TNC published this, pretty sweet document that provides a framework for, you know, the eventuality of, of restoration, activities and the, kind of the hurdles and questions that need, critical questions that need to be answered before we get to that point.

[00:45:59] But, yeah, for us, every single day that the pycnos are here in the wet table and alive is, something learned. it’s a step. we’re setting precedent. we’re utilizing, new systems, recirculating systems so with this first cohort, I think it’s just learn everything we can, be better prepared for the next.

[00:46:24] round of larvae that might be coming around it’s just building protocols at this point we’re chipping away, but there’s a gazillion questions that we could pursue and answer with the next round. So, I mean, yeah, stay tuned.

[00:46:42] Michael Hawk: And among your, the partners in this endeavor, you mentioned a few of them. do they have similar, Aquaculture setups and maybe looking at different aspects, different angles

[00:46:52] Reuven Bank: the Pycnopodia Recovery Working Group encompasses many different partners, some of whom, like Dr. Alyssa Gehman at the Hakai Institute and the University of British Columbia are focused specifically on the disease ecology of, sunflower stars and sea star wasting syndrome.

[00:47:07] Others are interested in, larval biology of sunflower stars and then we also have other partners here in California who are growing out siblings from the same cohort that was spawned on February 14th down at Birch Aquarium in Scripps. So, the Pycnopodia Recovery Working Group includes partners who are doing things.

[00:47:25] Similar to us, as well as those who are focusing on far other, more specific questions regarding aquaculture, or policy, or other efforts that will be crucial to the restoration of sunflower stars.

[00:47:38] Andrew Kim: I think generally speaking, every aquaculture system is different. And in the case of Sunflower Stars, One of the identified, Items , is to, not put all your eggs in one basket. we have different institutions with, different infrastructure, access to flow through seawater versus recirculating versus, any number of things.

[00:47:58] and yeah, we’ve kind of had this opportunity to do sort of a natural experiment, nothing like extremely rigorous or replicated, but the Pycnopodia ended up at five different institutions with varying degrees of, success, mortality, and yeah, we’re lucky at Moss Landing seemed to be, a really good place for whatever reason to grow, pycnopodia, larvae, and juveniles,

[00:48:24] Michael Hawk: if you were to be ready, like just from a population standpoint in the lab to be able to start doing trials of putting. the sea stars back into their environment. Are there missing pieces now because the environment has been so degraded? do you need the kelp?

[00:48:37] Do they need the kelp? or is that still a bunch of questions

[00:48:41] Andrew Kim: Outstanding questions.

[00:48:42] Reuven Bank: are outstanding questions that, potentially, trial efforts of outplanting might be able to uncover the answers to. In general, working towards the question of, bringing back our kelp forests, or trying to conserve the kelp forests that we have left in California, it wasn’t just one problem that led to their decline.

[00:49:01] It wasn’t, you know, oh, sunflower stars disappeared. That’s the only thing that was impacting our kelp forests. Let’s throw them back out there and solve this crisis. It took many impacts, many of them human caused impacts, on our environment to get us to the point where we are, and it’s going to take a collaborative and multifaceted approach to restoring.

[00:49:20] Andrew Kim: Yeah. I mean, you like to think that theoretically, you know, hopefully just putting the sunflower stars out there will take care of the problem, but there might be things that we’re not considering. And so, yeah, one of those things, you know, other than just in ocean trials, we might be able to do smaller scale laboratory mesocosm studies to help model how these interactions might play out.

[00:49:43] and to shift an urchin barren back to a kelp forest actually takes more effort than it does to turn a kelp forest into an urchin barren. Somewhere around 7 urchins per square meter is enough to shift a kelp forest into a barren. But anywhere from, 1. 2? urchins per square meter is needed to shift back to a kelp forest, so it’s almost like a higher effort input to move it back the other direction as well.

[00:50:18] Michael Hawk: could imagine too that, like, along this pathway of like some, know, future state where everything is great again and all the things would have to go there. there’d be a milestone along the way of you have sunflowers, stars, Surviving and, and reproducing in the wild. And maybe that’s just a couple pockets.

[00:50:35] But, like, there are these milestones along the way that, It’s easy for me, when I’m thinking about this, to jump to the, to the wonderful, possible in state decades down the road.

[00:50:45] Andrew Kim: Hope not decades, but yeah, I mean, and that’s the cool thing about kelp, right? Is that, I mean, in the case of like bull kelp, it’s an annual species. And so theoretically, we could have this like rapid recovery, right? You could go from barren to canopy in a year,

[00:51:03] Michael Hawk: I love to hear that. You’re right. And, that gives me a lot more yeah.that’s why, we’re all here doing this because we feel like We can help facilitate this recovery within our lifetimes, our working lifetimes,

[00:51:18] Yeah,

[00:51:19] I guess some of my pessimism came from the fact that we still have warming ocean temperatures and we still have some of these other things that are not, there’s no quick fixes for that.

[00:51:29] Andrew Kim: Yeah. And that’s going to be a continuing challenge.

[00:51:32] Reuven Bank: And having this really unprecedented aquaculture community for a species that was traditionally overlooked in the aquaculture setting is really exciting. Can potentially be really important to maintain even after initial out planning occurs because if in the future diseases such as sea star wasting syndrome sweep through the population again having the infrastructure in place and the knowledge base in place and The networks established could help us with future Conservation efforts to jumpstart them a little faster than the already torrid pace.

[00:52:09] Andrew Kim: and Echinoderms are actually interesting ’cause they’re kind of responsible for like ecosystem, collapse and saving playing out in different ecosystems around the world.

[00:52:18] Like, you know, in coral reefs you have crown of thorn sea stars that are like destroying reefs. And then you have another places urchin disease that is affected the edema urchins that are like. important for grazing the algae that’s smothering coral reefs. And so like there’s various kind of disparate, echinoderm conservation and restoration related activities in aquaculture, happening around the world.

[00:52:42] Reuven Bank: Yeah, and a lot of times what you’ll hear from folks is, antipathy or blame towards the purple urchins themselves for, you know, in mass raising through kelp. But purple urchins are a native species and serve an important role in a healthy kelp forest environment. It’s the fact that Sunflower Star has disappeared as one of the few major predators of purple urchins that has thrown this ecosystem.

[00:53:06] Out of balance, which is the problem. But, uh, we try to avoid Urchin vilifying here at the lab because they’re one of our, fellow echinoderms needed for a healthy kelp forest.

[00:53:15] Michael Hawk: I’m thinking about where I grew up in the Midwest and how foreign ocean systems and things like sea urchins and sea stars were to me.

[00:53:25] How else do you see this as important and relevant to folks who maybe don’t live and work here by the ocean?

[00:53:34] Reuven Bank: I think that the rapid growth and progress of a community based organization like Sunflower Star Laboratory shows just how much agency we each have. to impact for the better the environment around us. Whether it’s, a community park in the middle of the U. S. in Indiana that you’re trying to save, or whatever local environment or conservation project is important to you, our organization only exists because inspired members of the local community decided to take action and throw their effort behind a common cause.

[00:54:07] So, collectively, the impact that we can have on our environment can be transcendent, regardless of where you are living or what you care about.

[00:54:13] Michael Hawk: Is there anything else that we’ve missed that you want the audience to hear about with respect to your work, the lab, sea stats, comes to mind?

[00:54:24] Reuven Bank: I think there’s a couple of things that are really cool about Sunflower Stars that would be fun for folks to know. One of them is that Sunflower Stars are very different from us and from marine mammals like sea otters, we have really high metabolisms, especially if you’re a sea otter living in the cold ocean, trying to maintain your internal temperature.

[00:54:45] your energetic needs are very different than a sunflower star. And sunflower stars, laboratory studies have shown, don’t discriminate between a starved urchin that is basically devoid of gonads. If a human cracked that urchin open and saw there was no uni, we wouldn’t get much for dinner from it.

[00:55:01] But a sunflower star can, Eat both healthy or starved urchins, and then preliminary results that were shared at the Western Society of Naturalists conference this past fall demonstrated that they actually grow equally well off of both a starved urchin or a healthy urchin, from those environments, which is really cool in theory to think about the potential restorative power of being able to live and grow off of urchins that are in a barren environment

[00:55:27] Michael Hawk: I would love to see the lab if you think we’re ready to do that.

[00:55:30] Andrew Kim: sure.

[00:55:30] Reuven Bank: Take us away.

[00:55:32] Hey Catherine. Hey. We have folks coming into the lab who were here maybe just a couple of weeks ago and say something similar to what Catherine said about seeing the progress because you’re watching the stars just grow up before your eyes.

[00:55:48] Michael Hawk: Tell me what I’m looking at here. it’s a big tub.

[00:55:50] Andrew Kim: Yeah, so we’re looking at a recirculating wet table with tubs containing individual juvenile sunflower stars.

[00:55:57]

[00:55:57] Michael Hawk: Basically we just have seawater that gets pumped through these containers And recirculates through a series of filters, and chillers to keep the water temperature stable and,

[00:56:09] What’s your target temperature?

[00:56:11] Andrew Kim: 15.

[00:56:12] Michael Hawk: Is this literally water that you got from, like from the Harbor here or?

[00:56:16] Andrew Kim: No, it’s actually, we’re, lucky to be down the road from Moss Heading Marine Labs, which has a aquaculture facility. there’s a seawater intake about a quarter of a mile offshore at about 40 feet of seawater. And it comes in, it gets filtered through some sand filters, and then it gets brought in here to these header tanks.

[00:56:32] the header tanks are then further filtered and UV sterilized before they get entered into the

[00:56:37] Michael Hawk: Okay.Makes sense. you wouldn’t want a pathogen or something getting in here.

[00:56:41] Reuven Bank: Our water is coming from the ocean at some point. We’re not making it in house, but we’re also not a flow through system. So we have recirculating water going through our system, being filtered and put back in. And filtered many times with many different processes before it makes it into our lab. Yes, our laboratory manager, Vince, is a big fan of a particular anime show.

[00:57:05] So many of them have unofficial temporary names that are, related to that. We’ve got, Kaseki over here, Pippi, Kinro, various ones. Hannibal is one of the few that wasn’t named from that particular show, which one of our principal donors came into the lab, when Hannibal happened to be munching on one of their siblings.

[00:57:26] Because sunflower stars, like many, uh,marine species, can be cannibalistic in their early, juvenile stages, which makes sense if you’re a juvenile sunflower star. You and thousands of your friends just settled in the same general area, so you get a snack and you reduce the competition around you for other food sources.

[00:57:45] But once they get to a slightly larger size, they’re pretty gregarious and actually like to hang out with each other. But we’re being extra cautious keeping them apart

[00:57:56] Michael Hawk: that’s one there

[00:57:57] Reuven Bank: That’s Hannibal right

[00:57:58] Michael Hawk: Hannibal. Yeah.

[00:57:59] Reuven Bank: Yeah, so Hannibal and some of the other larger stars in our facility are now over 50 times larger than they were when they first settled in the juveniles.

[00:58:06] Hannibal is over an inch and was about half a millimeter when Hannibal first actually settled from larval stage into juvenile.

[00:58:13] Michael Hawk: Wow. And then What am I looking at there?

[00:58:17] Andrew Kim: are some crushed up urchins that were also cultured down the road, at Moss Landing Marine Labs.

[00:58:22] So you’re looking around and you can see a variety of different sizes. but these are all full siblings, born on the same day. From the spawn that happened at the Birch Aquarium back in February.

[00:58:33] Reuven Bank: About six months post fertilization and about five months post settlement. Because When our organization started, we were mostly working with local echinoderm species. Echinoderms being the general group of animals to which sea stars belong. they have five point radial symmetry, so if you cut them into five parts, they would all look similar to each other.

[00:58:55] but we were working towards the capacity to actually grow sunflower stars for conservation work. And some of the work that we do here at Sunflower Star Laboratory is not just in the lab itself. We also coordinate amongst partner institutions part of the Pycnopodia Recovery Working Group. Pycnopodia is the genus name of Sunflower Stars, which is a consortium of non profit institutions, research institutes, universities, government agencies who are all working together along the same road map to restoring sunflower star populations and trying to help our kelp forest.

[00:59:31] And so, we coordinated with a number of different partners, including Birch Aquarium at Scripps, Aquarium of the Pacific, the San Diego Zoo and Wildlife Alliance to spawn and cross fertilize This broodstock from Birch Aquarium on February 14th, Valence Times Day, fittingly enough, the cupid cohort, and those fertilized eggs were then sent to a number of different institutions across California, including Maasai Marine Labs, Cal Academy of Sciences, and others.

[00:59:57] Michael Hawk: doing the math, six months, they’ve gone from half a millimeter to about an inch.

[01:00:02] Andrew Kim: they’ve gone from sperm and egg,

[01:00:04] Michael Hawk: yeah, true.

[01:00:05] Reuven Bank: Sperm and egg to two millimeters, back down to half a millimeter to their current size, because the larval sunflower stars are actually from tip to tip larger than when they first settle. I think Andrew’s directing us to a partially completed mural that we have on the wall of the lab that shows the life cycle, and no one more qualified to take us through this than Andrew.

[01:00:23] Andrew Kim: You can think of Pycnopodia, or echinoderms in general, and lots of, like, spawning, marine invertebrates with larval cycles as having, you know, two kind of, like, distinct phases of their lives and so, Pycnopodia are broadcast spawners.

[01:00:39] They release sperm and eggs into the water column, and there are distinct males and females. females can release, tens of millions of eggs, per spawn.

[01:00:48] So we have eggs that are fertilized, and then they, the cells continue to divide, and they turn into this, blastula, and they have, the beginnings of an anus, and a mouth, eventually, and then they turn into this, peanut shaped, larva called the bipinaria, which has this bilateral symmetry, and they’re cruisin around, they’ve got these ciliated bands which they use to swim around in the water column.

[01:01:10] At that point they’re capturing, small particulate organic matter

[01:01:15] Michael Hawk: About how big are they at that point,

[01:01:17] Andrew Kim: they’re probably from like tip to tip, couple hundred microns. so very small, maybe just barely visible to the naked eye as like a pinprick. and then as they grow, as they eat and grow, they start to develop these extra, limbs and structures.

[01:01:33] And they eventually, turn into a Brachiolaria larvae, they put a lot of energy and time developing this structure called the Brachiolar apparatus, they’ve got like a suction cup that they can

[01:01:45] grab a hold of stuff with.

[01:01:47] it’s got these sticky cells. I

[01:01:50] mean, they’re, they’re just like fascinating and alien like little larvae.

[01:01:57] Reuven Bank: the diagram where it looks almost like a football with a bunch of noodley arms coming off of the sides of it.

[01:02:02] Andrew Kim: At this point, by the time they’re close to settlement, they’ve got a fully formed juvenile rudiment, which is essentially the baby sea star that’s growing inside of, like, the head of this thing. larvae is kind of like the spaceship, and the sea star, the juvenile rudiment is kind of like the alien living inside the spaceship.

[01:02:19] And, yeah, eventually when the rudiment is fully developed, they encounter the right sort of cue, or substrate, they can grab a suck themselves down onto it and they go from, like Reuven said, this two millimeter ish. Very visible

[01:02:38] larva to, a shrunken down little, sea star that emerges. It’s

[01:02:43] a pretty, like, dramatic thing that happens, metamorphosis.

[01:02:47] and then they settle out, and they are essentially They

[01:02:52] Reuven Bank: have that

[01:02:52] pentaradial symmetry. They

[01:02:53] Andrew Kim: look like a five armed sea star. but then they settle and they cruise around and they’re pretty immediately predatory. they want to start eating stuff.

[01:03:02] Reuven Bank: And our stars now, where they are about five months post settlement, some of our largest ones are somewhere between like, 2.

[01:03:09] 6 and 3 centimeters right now, and they’re working on arms number 9 and 10

[01:03:15] Michael Hawk: Okay. I was going to say one I saw over there had six, so I was wondering how that

[01:03:19] Reuven Bank: Yeah, if you take a look really closely you’ll probably see about eight big arms and two tiny ones sticking out Sprouting from in between some of their other arms as they grow them out So they started off at five and some of them are now double the number of arms as when we were initially settling them

[01:03:33] We’ve got Hannibal chilling on a rock right

[01:03:36] Michael Hawk: you see the little arms

[01:03:37] Reuven Bank: You can see the arms, and you can also see the eye spots, if you zoom in really closely there. So, Sunflower Stars, even as juveniles, at the tip of each of their arms, they have these eye spots.

[01:03:47] So as an adult, they can have up to 18 to 24 different eyes. They can perceive differences in, you know, light, darkness, shadows.

[01:03:55] Andrew Kim: we should just do like a walk around the lab really quick, kind of like

[01:03:59] the general, yeah the gist, because you know we’re here at Sunflower Star Lab, we’re trying to

[01:04:04] Michael Hawk: blocking

[01:04:05] Andrew Kim: and build protocols for scaled up aquaculture methods for Pycnopodia. And unlike other things like Abalone or oysters, other traditionally kind of aquacultured things. pycnopodia are predators. and growing pycnopodia requires growing the food for pycnopodia as well as the food for the food for pycnopodia.

[01:04:31] And so, it’s a triple trophic. Bonanza in here. It starts with our microalgae cultures.

[01:04:37] Reuven Bank: so we’re growing this species of red, microalgae called Rhodomonas lens.And, Echinoderm larvae do really well on it.

[01:04:46] Michael Hawk: So we’re looking at, multiple jugs, or I see, looks like maybe dates on them?

[01:04:52] Andrew Kim: and it just, looks like we’re brewing up some kombucha

[01:04:54] Reuven Bank: Vince has been

[01:04:55] homebrewing algae, here at the laboratory. And you can see shades going from very light brown to kind of an orangish hue to more of a dark brown. And so, you have a higher density of these microalgae in the the darker colored growlers that we have on the shelf. And there’s dates on them, which refer to when they were split, I believe.

[01:05:15] And we’ve got our lab manager, Vince, is uh, working on, some of the algae cultures right now.

[01:05:21] Michael Hawk: Thanks

[01:05:22] for

[01:05:22] accommodating

[01:05:23] my little

[01:05:23]

[01:05:23] Vince Christian: oh yeah, my pleasure, yeah, glad to have you.

[01:05:26] Michael Hawk: I didn’t grow up near the ocean. I grew up in Nebraska, I was born in Chicago. so, all things ocean are, it’s like, at age 40, I’m a little older than 40 actually, I’m discovering this whole world that I kind of ignored for so long.

[01:05:40] So, that’s kind of where I’m at right now.

[01:05:42] So then, you’re growing the algae here, and what happens next?

[01:05:46] Vince Christian: We kind of keep a continuous culture. we’ve got seven, for each day of the week. So we have a lot of replication, but we take the oldest one, which, we’ll do this one today, and we take, two and a half liters of seawater, which we’ve sterilized, in sterilized containers, We put a milliliter of bleach to make sure there’s no bacteria in the water.

[01:06:09] And then we’ll, dechlorinate it and then add some fertilizer to it. And then we’ll top it off with the oldest algae and then that will be the newest one. So we did this one yesterday and so we just have them on a rotating basis.

[01:06:23] Reuven Bank: And maintaining stable algae cultures can be the bedrock of an aquaculture system, because like Andrew was saying, this is the food for the food that we will then be feeding to the sunflower stars. So, in many ways, we’re kind of trying to recreate an ocean system in a laboratory environment.

[01:06:41] so we’re working with California Department of Fish and Wildlife looking to be able in the future to import larvae from other states, such as Omaha with the Henry Doorly Zoo, into our laboratory here.

[01:06:54] Right now, the ones that we have inside of our laboratory are all internal to California. Actually, these were internal to the Birch Aquarium at Scripps where both the male and female were spawned and cross fertilized. But, we are working towards actually bringing those larvae in cooperation with CDFW across state lines so that we can have perhaps more frequent cultures and, a more diverse array of broodstock.

[01:07:15] Michael Hawk: So what happens then next here? is there a different tank you take it to?

[01:07:19] Andrew Kim: and so, you’re here now while we’re kind of in

[01:07:22] the process of,

[01:07:23] The finishing stages of

[01:07:25] putting together

[01:07:25] our larviculture system, which was like, it’s the state of the

[01:07:30] Reuven Bank: the art This is very fancy. Some professional aquarists are jealous of the setup that we have in our lab. So we have

[01:07:35] Andrew Kim: The idea is that, we need to

[01:07:37] have essentially a conveyor belt of urchins and other prey items that we need

[01:07:44] Michael Hawk: I was kind of assuming you’re starting the conveyor belt, but some of the pieces are still being assembled.

[01:07:50] Andrew Kim: and So the algae cultures have been going for over a year, they’re just perpetuating, and there have been, you know, smaller scale, Echinoderm larval culture. efforts that we’ve had on the table,

[01:08:00] Michael Hawk: by doing that right now, even if you don’t have some of the downstream pieces, like you don’t have larva constantly coming in or some other things coming in, you’re getting to practice, you’re refining the process, you’re figuring out the best, best methods.

[01:08:13] Reuven Bank: we have had intermittently larvae in the lab as well, so we have utilized our, microalgae cultures to feed them, but we’re talking about a pretty tremendous scale of the system that we’re looking at here. So having this in place for once, we’ve really Start to exponentially increase our larval capacity will be really important.

[01:08:33] And to describe what we’re looking at here. We’ve got these Large cone bottom tanks which are coming up about to like mid chest height on us right now Which are filled nearly to the brim here with seawater. And if you want to talk a little bit about how we’ve got them plumbed

[01:08:50] Andrew Kim: Essentially what we’re looking at doing is running these tanks, in a paired design allowing larvae to swim back and forth between these paired tanks you know, part of larviculture and culture is like most of the effort of. Larval rearing and culture goes into just the cleaning practices, you know, along with providing adequate food and water motion.

[01:09:17] You just need to keep things clean.

[01:09:20] Michael Hawk: So at this point the audio got a little bit rough. Andrew described how the paired tank design allows the larva to swim to the second tank so that they can scrub down and clean the other tank.

[01:09:29] This innovative approach is much easier on the larva and the caretaker.

[01:09:33] Andrew Kim: It’s just the challenge is kind of like, what do you do once they settle and they’re highly cannibalistic,

[01:09:40] we’ve just got half the system currently plumbed and this will be like the first kind of wet

[01:09:45] run

[01:09:45] Michael Hawk:

[01:09:45] Andrew Kim: we have enough capacity here To raise over half a million, larvae at a time per set of tanks? Yeah,

[01:09:54] Michael Hawk: so you’re gonna have a million capacity of a million here. Yeah. When you’re done. . Yeah.

[01:09:58] Andrew Kim: we don’t have to be married to this idea of, Having them paired tanks, we can’t, there are also ways to run them as single tanks. so, you know, you could think of potentially if we were to really try to maximize the space available, then we could theoretically double that capacity as well.