#80: El Niño (ENSO) and Ocean Temperatures – Nature's Archive

Summary

Have you heard of El Niño? Some people call it the single biggest influence on winter weather in North America. But what is it, and how does it work? And we’re in an El Niño event this year, and it’s going to affect our weather (and ecology!)

There is always much confusion about El Niño, what it is, why it occurs, and how it might alter our weather in the coming seasons.

Today’s episode looks at El Niño, which is one part of the El Niño Southern Oscillation, or ENSO. Consider this a primer – an accessible look at some of the mechanisms and impacts of El Niño, and how and why it can impact weather from India to California and beyond. And we also include a few ecological tidbits here and there.

In order to give El Niño its due, we also cover some of the basics of how oceans influence weather.

I tried hard to pack a lot of information into 50 minutes, along with a lot of analogies to help reinforce some of the points. Let me know how I did! And of course, these are very complex systems, so there is much that I couldn’t cover.

Looking ahead, we will have an expert climatologist later this year, so this episode will serve as good background for some of that conversation. I also have interviews with a dendrochronologist (tree ring expert!), a wildfire episode with an ex-firefighter, and an episode on nocturnal animals. So be sure to subscribe to the podcast in your favorite app to ensure you don’t miss future releases.

Did you have a question that I didn’t ask? Let me know at naturesarchivepodcast@gmail.com, and I’ll try to get an answer!

And did you know Nature’s Archive has a monthly newsletter? I share the latest news from the world of Nature’s Archive, as well as pointers to new naturalist finds that have crossed my radar, like podcasts, books, websites, and more. No spam, and you can unsubscribe at any time.

While you are welcome to listen to my show using the above link, you can help me grow my reach by listening through one of the podcast services (Apple, Google, Spotify, Overcast, etc). And while you’re there, will you please consider subscribing?

Links To Topics Discussed

People and Organizations

Daniel Swain – Weather West, YouTube Office Hours

Jet Stream Alignment in ENSO Scenarios

National Weather Service CPC ENSO Report (PDF)

Credits

The following music was used for this media project:

Music: Spellbound by Brian Holtz Music

Free download: https://filmmusic.io/song/9616-spellbound

License (CC BY 4.0): https://filmmusic.io/standard-license

Artist website: https://brianholtzmusic.com

Transcript (click to view)

Michael Hawk owns copyright in and to all content in and transcripts of Nature’s Archive Podcast.

You are welcome to share the below transcript (up to 500 words but not more) in media articles (e.g., The New York Times, LA Times, The Guardian), on your personal website, in a non-commercial article or blog post (e.g., Medium), and/or on a personal social media account for non-commercial purposes, provided that you include attribution to “Nature’s Archive Podcast” and link back to the naturesarchive.com URL.

Transcript creation is automated and subject to errors. No warranty of accuracy is implied or provided.

Transcripts are automatically created, and are about 95% accurate. Apologies for any errors.

[00:00:00] Michael Hawk: Hey everyone. Have you heard of El Niño? Some people call it the single biggest influence on winter weather in north America, but what is it and how does it work? Well, that’s the topic for today and in order to properly get into El Niño, we need to talk about ocean temperatures and weather more generally, just a little bit. Today’s guest is well me. So I’m not an expert on these topics, but I know the basics and enough to be dangerous, but more importantly, I do have an expert climatologist interview coming up soon. So I think this episode is going to serve as a great primer of sorts for that interview. That we’ll probably be out towards the end of the year. Also. I’ll work in a little bit of ecology here and there. In fact, the name El Niño has an ecological story. That’ll tell you about.

[00:00:44] And looking ahead, we have more great nature’s archive coming. We have an episode on wildfire, including prescribed burning and wildfire communication. We also have. Uh, great guest discussing dendro chronology. That’s a big word, but it simply means the science of tree rings. And I have to admit it turned out to be much more complex and even more fascinating than I ever imagined. There’s so much to be learned from tree rings. And do you want to learn about nocturnal nature? The animals and their adaptations to be active at night. That’s very interesting. And that’s coming up soon as well.

[00:01:18] And the really big news where I’ve been spending a ton of time lately is our jumpstart nature podcast launches on Monday, October 2nd. This podcast is very different from nature’s archive. Aside from the fact it does discuss nature topics. So here are a few of the differences, every episode dives into one topic, but it has the help of multiple guests and it reveals myths and surprises of that topic all in a concise and entertaining narrative format.

[00:01:44] So instead of a free form interview, like nature’s archive, this is actually produced and put together to tell a story with the help of all of these experts. And in fact, our host is Griff Griffith. You probably know him from past nature’s archive episodes. so you can imagine that he’s going to be a great narrator and host of the show So get ready to learn about the surprising truths of lawns and native plants. Why feeding birds may not be the win-win that we think it is and how you can turn it into a win-win actually. And we’ll learn about the surprising psychological concept that’s driving biodiversity loss and how plants and animals need connection and community to survive as well. Lots of great stuff. Can’t wait to share it with you. This is our pilot season is what we’re calling it because we want to learn from you and learn from the audience, what you like and how to make it better in the future. I literally have a set of slides with proposals for something like 60 additional topics that I think are all very compelling. I really want to make this work, so please check it out. Our trailer is already up. You can subscribe right now. And once we launch on the second, I would love it for you to leave feedback and share it and do everything you can to help me continue to make these podcasts.

[00:02:56] All right. If you’ve been listening to me for a while, you’ve probably heard me comment on the fact that I’m a little bit of a weather nerd among my various nerd hobbies. And I wear the crown of nerd proudly because I love to dive. Moderately deeply into topics and really get into the weeds with them. And I think I have a knack for learning. , I don’t always have that knack for remembering. So this episode was a lot of fun to put together because it forced me to dig deep and, uh, you know, remember some of the concepts that we’re going to talk about. living in California, we have boom and bust cycles of precipitation. And for that reason, I’m particularly fascinated with El Niño, which is a cyclical fluctuation in ocean temperatures. And it has a global impact on weather and animals for that matter. And more accurately El Niño. When we’re, when we’re talking about this, it’s. It’s one part of a cycle that is more formally called the El Niño Southern oscillation or in so E N S O.

[00:03:56] Here in California, El Niño events more often than not bring extra winter rains, especially in the Southern half of the state. Sometimes these rains can also be quite excessive leading to flooding and landslides and other impacts.

[00:04:10] And whether you live in Nebraska or New York or British Columbia or Florida, or any point in between. You’ve probably heard your local meteorologist talk about how El Niño affects your weather as well. And the El Niño this year, it looks to be. A pretty big one. The current forecast is moderate, maybe even strong. So I think this is a great time to explain exactly what this means, because the impacts of El Niño are right around the corner.

[00:04:38] I think to really get into in, so though I’m going to start calling it in. So maybe I’ll flip back and forth between El Niño and, and so, um, it’s important to first understand why and how oceans play such a critical role in weather. And I cannot stress that enough oceans, disproportionate impact to global climatology. First. Did you know that water is actually denser than air? Well, you probably did, even if you haven’t thought about that fact recently, I’m sure you know, this at least intuitively because after all. If water was less dense than air it, wouldn’t collect in depressions on land and form lakes and ponds and oceans. That’s a form of liquid water being more dense. Some of, you might be saying, but wait, water vapor is actually less dense than air and that’s actually true as well. And this is one of the amazing facts about water. I was actually really tempted to do a rapid fire. Like this is why water is such an amazing thing and all of the remarkable properties that it has, but I’ll spare you from that. Uh, but water vapor is the gas form of water. It’s less dense. Which is why when it evaporates, it actually rises into the air. Anyway, back to liquid water. Which is roughly by the way, 800 times denser than the air near the surface of the earth. I say roughly because things like salinity and temperature and some other factors can. Minorly effect that density. So remember 800 times denser than air. That’s much more dense. This density is an extremely important factor in weather because it means that water can also store a whole lot more energy than air. So the denser, the material, generally, the more energy it can store and what, we’ll talk a bit more about that. And it takes much more energy in turn to change the temperature of water than it does to change the temperature of air. So here’s a simple example. Anyone who’s ever owned an outdoor swimming pool or maybe used an outdoor swimming pool? Probably recognizes that it takes a while for the water to warm up in the spring and early summer. And it might retain its warmth. Even when the air is cooler at night or like in the late summer when the weather is during the cool down, but that pool may stay warm just a little bit longer. If like me, you haven’t owned a swimming pool. You can see the same property with other dense materials like stones or boulders, or maybe even a concrete driveway. It retains more heat energy at night and may still feel warm. Even when the ambient air temperature has cooled off. This is also why you often see snakes on roadways in the evening. So the air starts to cool down. They want the thermo regulator, they want to transfer some of that heat energy from the road into their body so they can remain active a little bit longer.

[00:07:27] But that’s just part of the picture when it comes to water. Not only is water denser than air. It has this other amazing property where gram for gram. It can store more heat than most other materials on earth. Yes, water, simple water that we deal with every day. So in physics, The unit of heat capacity, the amount of heat that can be stored, it’s called specific heat. And one gram of water has about four times the specific heat of one gram of dry air. Uh, four times. So recall that water is 800 times denser than air. And has four times the heat storing capacity. So like back of the envelope, math, that’s like 3,200 times the heat in the same amount of space as air, at least the heat. Storing capability. So now imagine, and by the way, that number is not quite right, but it gives you a rough idea. Now. Okay. Imagine earth. Take a step back, pretend you’re an astronaut floating out. by the space station, you see earth passing below you. And as you’ve likely heard the oceans cover nearly 70% of the surface of the planet. So that’s the majority of what you’re seeing right now, as you. Um, rotate above the earth as this astronaut. And those oceans, what you can’t tell, they run very, very deep. The Mariana trench, the deepest part of the ocean is about 36,000 feet deep. Compare that to Mount Everest, the tallest part, which is 29,000 feet tall. So the deepest part of the ocean is deeper than the tallest part of the crust of earth. Now some estimates are that the median depth of our oceans are 12,000 feet. That’s very deep. It’s amazing. So, yes, we have a lot of heat storing capacity in this huge volume of ocean water. 70% of the earth. 12,000 feet deep. That’s a lot of water. The deep ocean water is not as warm as the surface of the water. But in turn, you can think of the ocean as a giant heat sink. So they have this capacity to store so much heat. On an ever increasing basis, it can just keep absorbing and absorbing and absorbing. So, this is kind of an abstract concept. We haven’t really talked about how all this heat really affects the weather. So I’m going to start with a real simple example. At many people living on the west coast have probably experienced. So where I live, I’m in San Jose, California. I’m about 25 miles from the Pacific ocean. And the Pacific ocean, just for your bearings. It’s west of me and here in the Northern hemisphere and the mid-latitudes of the Northern hemisphere, most of our weather comes from the west. So it is coming over the Pacific ocean. Towards me. So it turns out. That there are huge ocean currents that shuttle water at continental or even oceanic scales. . Imagine that the size of an ocean and their occurrence that are flowing and channeling water. Throughout the whole. Perimeter or length of that, that ocean. Along the west coast of the us. There’s the California current, which carries water from the cold north Pacific down through California, along the coast. Uh, and kind of all the way down to the Mexican coast, it at times departs from the coast. And you’ll see a little as a result, some warmer temperatures say San Diego or, or those areas once in a while. Um, there are some sub currents I’ll say, but in general you have the California current taking this cold north Pacific water along the California coast. Since this water originates from far up north, as I said, like three times now, it’s cold. So the way that people generally measure water temperature is at the surface. They’re called sea surface temperatures. Often abbreviated SSTs and the sea surface temperatures near San Francisco, which is just a few miles north of me. Uh, but I think a lot of people have a rough idea as to where that is. usually those temperatures range from the low fifties to the low sixties Fahrenheit. Even all the way down. In San Diego temperatures usually only range between the high fifties to high sixties, but like I just said, There have been more and more. Uh, departures from that in San Diego, where seventies are starting to become a summer normal in San Diego. But. What will, you know, for reference we’ll remember high fifties to high sixties as what has historically been normal? Compare this to Savannah, Georgia, which is about the same latitude as San Diego, but all the way over on the Atlantic coast, the east coast of the United States. There’s a different current system there that brings water up from the south. So their winter sea surface temperatures are actually kind of similar to San Diego in the upper fifties to low sixties, slightly warmer, not much. Uh, but they balloon into the low to mid eighties in the summer. So that’s a solid 10 to 15 degrees, maybe even more warmer in the summer. And this is partly because as I said, those coastal currents, it’s a different system bringing water up from the south. So back to my point. Here in San Jose, our weather comes from over those relatively cool ocean waters. As we just established there in the fifties or sixties. Now, this means that in the summer, Warm summer air that’s traveling over the ocean. It. Traveled over those cool waters and it actually gets cooled. So these systems are coupled. Air and oceans while they’re different mediums. They touch, they interact. There’s winds, there’s waves of things going on there. And what results from that is the ocean will readily absorb heat from anything that touches it, including the air, it traps a lot of that heat. It also cools the air as a result. So the air that comes across is getting cooled. So the side effect of this cooling. Is that clouds and fog forms. Anyone who’s been to San Francisco in the summer. Knows that sometimes those may and June, and even sometimes. July August. Days. Can feel almost like winter, surprisingly cold, especially right on the coast in the fall. And the fog prone areas. So this fog it’s condensation. And you can see. The process of condensation. Very easily. so all you gotta do is get a glass of water and put a lot of ice in it. And. Anything, any air that touches that cold glass on the outside as it’s circulating around. When it touches that cold glass, that air is going to cool as well. It’s going to transfer its heat to the glass and the coolness will be transferred back to the air. And this is going to force the air’s water out as condensation. So slowly little drips of condensation form. Along. The. Edge the perimeter, the outside of that glass.

[00:14:30] By the way, another quick aside, you can also see the inverse of this in your car. If you have condensation on your rear windshield, you can turn on your rear window defroster, which is often it’s a series of little wires that you’ve probably noticed running through that rear windshield. I guess maybe technically it’s a window, not a windshield, but in any event, By heating up those wires. You halt the process of condensation because now the glass is warmer. The air immediately next to the glasses, warmer and air that touches it warms instead of cools. And this also triggers the opposite effect. So not only does it halt condensation. It evaporates the water. That is sitting on that glass. So I think that’s pretty cool. It’s a, it’s an easy way to understand what’s happening with fog. Forming is air is cooling down and it’s forcing this condensation, which creates little droplets of water suspended in the air. Uh, fog or clouds. So back to the example in my home of San Jose and the west coast in general. So we have. One of the big effects of oceans I just described. And that’s much of the west coast sees low clouds or fog in the summertime. When we have these, prevailing flows of air that, uh, caused the cooling and caused the fog.

[00:15:48] So I told you I did include some ecology here and there. And here’s a big one, literally a big piece of ecology. Coastal redwoods. The tallest trees on earth. side note, I was just reading a story that was saying that the tallest Redwood is 380 feet tall. And when scientists did some math to figure out how tall could a Redwood actually grow. The limiting factor seems to be the ability to transfer water through capillary action all the way up to the top of the tree. And the. This study anyway, claimed that 380 feet to actually very close to the limit. Maybe it could hit 400 or perhaps 420 feet, but, but very interesting. All right. So coastal redwoods, the tallest trees on earth. There are several plants along the west coast, including the coastal redwoods that have adapted over many thousands of years to take advantage of this. Climatological fog that we see. So using redwoods as an example, they have special leaves that caused the condensed water to drip down to the ground, and then they couldn’t absorb that water through their roots. So it kind of like turns the fog into light rain. And they also have only recently discovered maybe a decade or two ago. It wasn’t that long ago. other tiny leaves that have been shown to directly absorb water from the air. And they call this foliar uptake. So in fact, I read that they have an ability to absorb water through their bark as well, which is just amazing. Uh, an amazing adaptation that you would only see over eons and eons of adapting to persist in a given climate.

[00:17:28] So these three processes are basically drinking. The fog are all critical to the survival of coastal redwoods. the other piece of the puzzle, if you’re not familiar with, with these coastal redwoods that grow primarily in California, along the coast is that California’s summer climate is very dry. We don’t really get any rain in the summer. Very rare. And we do get this fog though. So it’s, you know, these redwoods have figured out how to take advantage of that.

[00:17:55] Okay. So we’re on our journey of talking about oceans and why they’re important before we get to El Niño itself. So circling back to our west coast fog and low clouds. Uh, recall the air has a lower, specific heat capacity, even water. And land. Has a lower, specific heat capacity than water as well. So on a summer morning. You know, we have this fog that has been pushing in from the coast. Land we’ll warm more quickly than the ocean. It has a lower, specific heat, meaning it can more easily warm up, more quickly warm up. So the warm air can hold. More water vapor as well. then cool air can. So this warming halts, the condensation, just like that defroster on the back of your windshield and it causes the fog to burn off.

[00:18:42] So, this is a very normal pattern. I’ll wake up with low clouds almost every day in the summer, even today here in September, low clouds. And then depending on how deep, uh, how much moisture, how much fog it can take a couple of hours to maybe even until 11 or noon or something like that for it to burn off.

[00:18:59] So I want to point out. There are some other factors here. it’s not just the California current that causes cool water along the coast. There are certain areas that are even cooler, and this is caused by a process called upwelling. So upwelling. Is basically deep water rising to the surface and I’m not going to get. Pardon the pun deeply into that topic here today. Uh, but there are certain points where this happens more than other locations. And, and interestingly enough, this cold water upwelling creates a kind of an eco tone of sorts where habitats change very quickly. And it’s usually a very productive part of the ocean where you see lots of life, along a cold water upwelling areas.

[00:19:43] Okay. Another thing to keep in mind is that once in a while, the weather doesn’t purely flow from west to east storm systems can kind of get backed up. There might be a blocking high pressure system or different things like that that can create a reverse flow. And when we have these rare off shore flows, we don’t get the fog.

[00:20:01] And in fact, in California, where, where it may not rain for months in the summer, these off shore. Events can be a very problematic from a fire weather standpoint. Uh, because it’s pushing all this humidity away. It’s allowing things to warm up more quickly. And it is a drying type of wind. So humidities can get to be exceptionally low. Uh, this can really amplify fire risk. So anyway, this idea, this scenario gives you an idea of how ocean influences weather and ecology, to some extent.

[00:20:33] So one more thing about sea surface temperatures before we get to El Niño, I know you’re probably like get to the point. I want to hear El Niño. Uh, so it’s currently the peak hurricane season in the Northern hemisphere. , I think this is a great example of a case where people have heard about. Ocean temperatures affecting whether that’s worth elaborating on a little bit, just so you have this, this background. So it’s true that. Warm ocean waters can fuel tropical storms and tropical storms or special types of storms are very different than storms that occur over land. So of course, to get a tropical storm or a hurricane, you need other favorable conditions too, but ocean temperatures are essentially the fuel of the storm. So, again, this is not, this isn’t a hurricane episode, but the short story here. Skipping some details is that the warm waters can sustain. What’s called a positive feedback loop in hurricanes. A positive feedback loop means that the system is self reinforcing. And feedback loops are a big part of climate. And this is a good example. And you can also have, by the way, negative feedback loops in certain situations where. instead of self-reinforcing, it’s kind of self destroying in a way. Anyway, remember heat is actually energy. And there’s plenty of water vapor over the ocean. And especially when it’s warm. Warming air. Rises. And it naturally cools as we’ve discussed, when it reaches cooler temperatures in higher altitudes. So this causes that warming, moist water over the ocean to condense. And a side effect of condensing water vapor. This is where the water basically gets forced out of the air. Is that it releases energy as heat as well at the same time. And I know it’s hard for me to wrap my head around. What’s actually going on here. If you want to geek out on this, it’s it’s called latent heat release and it’s basically. One of the requirements of the first law of thermodynamics. So the energy of the water vapor converts to heat when it convinces. So we’ll leave it at that for a moment. I stated more succinctly.

[00:22:45] Warmer oceans lead to more water vapor. Which rises re remembering that water vapor is less dense than regular air. And eventually when it gets high enough, it cools it condenses and it releases more heat. So this heat actually powers the storm. So with heat air continues to rise. Rising air lowers the air pressure. You know, these hurricane systems have extremely low pressures in the center, especially so lower air pressure creates a higher pressure differential. The air pressure. You know, changes more dramatically over a short distance. So that’s what. Air pressure differential refers to.

[00:23:25] So the atmosphere wants to equalize these air pressures. So it increases winds because gasses naturally want to equalize. They want to, uh, come together. The higher wind draws, more warm and moist air from the ocean surface from further and further away and more quickly. Continuing this feedback loop of water vapor, rising, condensing, warming, more winds, bringing more. Erin more fresh moisture, more warmth. So feedback loops are very powerful.

[00:23:55] Here’s a great example by the way of a feedback loop that just came to me as I speak into my microphone. If you’ve ever been speaking on stage. You’ll notice that it can only take milliseconds for feedback and a microphone to create this painful screeching sound. That’s when the sound of your voice coming out of the speaker goes back into the microphone, feeding back, causing a circular repeat of the sound. And this is what, why these storms can so quickly build up and also so quickly fall apart when they encounter land or some kind of adverse atmospheric winds that break down the structure, causing the feedback loop.

[00:24:29] Okay enough about hurricanes, but I think it was important to have this concept of how warm waters can really power storms as well. So let’s talk about El Niño.

[00:24:39] I first remember my local TV meteorologists talking about El Niño, probably around 19 90, 19 91, somewhere in that timeframe. And maybe you didn’t know I was that old or maybe I just have an exceptional memory at a very young age, but I’ll let you decide that. So, as I said before, though, the proper name is El Niño Southern oscillation or ENSO. And it’s the oscillation. That’s the key point here because sea surface temperatures oscillate in a very distinct pattern. That’s the core of what El Niño is, at least on the surface. So while it took until the late 20th century for El Niño and ENSO to reach the common weather vernacular, the effects were actually first documented as early as the 16th century. So this is not a new thing. Even if the term might seem relatively new to you. But what is it? So here’s an analogy. It’s the best I could come up with. , hopefully it gives you at least a surface level understanding. So imagine you have two friends sitting on a huge Seesaw. And one of them is named El Niño and the other is named LA Niña. And they’re at either end. So El Niño is sitting on the Seesaw near Peru and Ecuador. And LA Niña. Niña is sitting on the Seesaw. Way further west along the equator, maybe out near Indonesia. Approximately. And in this case, the Seesaw is a very narrow, narrow strip of oceanic water that stretches between these two people across the Pacific ocean. When El Niño sits on the Seesaw. Remember. El Niño is near Peru and Ecuador. All the warm water moves towards that area. And when LA Niña sits on the Seesaw. We out near Indonesia, the Warm water moves west in the cool water. Replaces the warm water. Back where El Niño is. So in this simplistic visualization. You can see the oscillation here, the El Niño Southern oscillation.

[00:26:37] But the sea surface temperatures are more of a symptom of a broader process. So similar to how your fever is a symptom to a systemic infection of your body. that’s kind of what we’re talking about here with, these water temperatures and in, so the ENSO process it’s fascinating and complex. And not only that other factors such as cold water upwelling can turn on and off at various points, if a dampening or amplifying El Niño. So there’s a lot at play here. So before we get deeper into El Niño, no, that I’m not getting into some of these confounding or amplifying processes that are also part of El Niño. There’s so much more to the story. There always is.

[00:27:18] So let’s start though by considering what happens in neutral conditions. So we’re not an El Niño, we’re not an LA Niña. So visualize what’s going on here. This is kind of a default condition. And in this case, there are persistent winds along the equator that blow from east to west. So for those of you in the mid-latitudes of the Northern hemisphere, this, this might be a little confusing because it’s opposite of what we generally experienced. So they’re blowing from east to west. These are the Tradewinds. And they’re generally consistent in equatorial regions around the globe. And by the way, interesting fact, there named the Tradewinds because of their historical importance in sailing, which permitted trade between different groups. So, as I said, Tradewinds are generally consistent and stable. This is because they are largely influenced by the earth rotation, which as you might imagine, the Earth’s rotation is pretty consistent and stable. Thankfully. This consistent push from the winds literally pushes the surface water. More and more west. It’s hard to imagine. It’s like really winds. I can push surface water. Yes, it does. It’s not just waves. It’s even more, uh, impactful than that. So it causes water. To pile up deeply in the west. There’s literally a slope on the ocean surface as a result. That’s right. The water is deeper on the Western end of this Seesaw. I was telling you about than it is on the Eastern end, in this neutral condition. And in fact, the water can be meters deeper, especially when, when we have a LA Niña event, but even in the steady state, it’s deeper. So my view, again, this is pretty wild to consider the ocean can be so much deeper. Because of the power and consistency of wind. And by the way, there’s a term for this slope, they call it a thermocline. at which also gives a nod towards the temperature aspect of it. So remember the warmer water is less dense than cooler water. So this consistent wind is pushing this less dense water on the surface. Westward in this non El Niño state leaving the cooler water behind. So basically we have an accumulation of deeper warm water in the Western Pacific equatorial region.

[00:29:35] So, depending on where you are in the Pacific, these water temperatures can fluctuate. Depending on where we’re at in the cycle as well. From anywhere from like four to seven degrees Celsius, even more in very rare cases. So that’s like seven to 12 and a half degrees Fahrenheit. And we’re talking about a body as big as the ocean. That’s all connected. All this water is touching other water. The fact that you can have. Water temperatures change like that is that’s a lot. That’s a lot of heat. That’s being transferred. As you can imagine water’s fluctuating and temperature by this much over such a large area. Can trigger a significant atmospheric response. So meteorologists, like to say, it’s a coupled system, the atmosphere and the ocean are coupled together because they’re exchanging heat. And there’s all sorts of things that go along with that. Most fundamentally. The winds and the broader circulation patterns that drive storm systems and hurricanes are what is impacted in the atmosphere when ocean temperatures change dramatically.

[00:30:37] As we said before, wind is the atmosphere’s attempt to equalize pressure. Air and high pressure systems tends to blow towards low pressure systems. And that kind of makes sense if you stop and think about it. There’s more pressure pushing the air towards the area that has lower pressure. That’s like pulling the air in, in a way. So the spinning of the earth also adds some spin to these air flows and there’s other dynamics that come into play. But that’s the general idea here is these air pressure systems are trying to equalize. In the inside neutral condition. Warmer water is accumulating in the Western Pacific and this leads to higher pressure in the Western Pacific.

[00:31:16] So for a variety of reasons. This steady state. Default state neutral state. I can stop the Tradewinds my weekend for some reason. And there’s lots of, again. Systematic reasons why this begins. But when the Tradewinds weekend, it could begin an El Niño cycle. This weakening of the creative winds might allow that several meters deep, warm water that comes slowly sloshing back towards Ecuador and Peru. Over itself. You know, it’s several thousand miles along that path. In some cases, the Tradewinds might even reverse rich can hasten this pace.

[00:31:53] You might be wondering why this warming and cooling occurs over this relatively narrow equatorial strip. This largely has to do with the global atmospheric and ocean circulations, which are driven by the earth spinning and the configuration of our continents. So we talked about the Tradewinds, which occur in this narrow strip. As well. That’s no coincidence. And the other unique thing here is there’s this vast area over the Pacific ocean. That’s relatively unobstructed by land. So take a look at a map. The Pacific is the largest ocean, and then you go. Uh, thousands of miles between south America and Indonesia with really no land. So that’s a, that’s why we have this broad area affected so dramatically.

[00:32:35] Okay. Let’s take stock of where we’re at in describing. ENSO. we have a normal condition where trade winds blow from east to west along the equatorial region. This vast area of the Pacific with no land obstructions allows these consistent Tradewinds to pile up water in the Western Pacific. And this water that’s being piled up. It’s the warm water that has risen to the surface and that’s, what’s being pushed. If and when a disruption to the Tradewinds occurs, the water can flow back to the east. And this can break various other systems, feedback loops other things in the atmosphere and in the ocean and speed up the process, possibly even leading to reversing the Tradewinds. And a rapid warming of the ocean temperatures in the Eastern Pacific.

[00:33:19] Sometimes, remember I talked about cold water upwelling earlier. That’s a thing down here too. And sometimes the cold water upwelling and the Eastern Pacific also stops. And that’s a whole other discussion as to why and how that happens. I won’t get into that now, but as you can imagine, if cold water is no longer moving to the surface and warm water is being pushed back in, uh, that can lead to a warmer condition than you might otherwise have.

[00:33:46] Because the ocean and the atmosphere are coupled, constantly exchanging heat. Uh, warming ocean means a warming atmosphere and vice versa.

[00:33:54] So depending on where we are in the cycle. You might see warming or cooling of the ocean anywhere along this huge equatorial stretch. remember. The Seesaw analogy from before.

[00:34:05] Now there are a whole bunch of other things that can happen at the same time that can either amplify or reduce this water movement and warming and cooling process. We talked about the cold water. Uh, upwelling a second ago. There are these things that you can look up that I’m not going to get into today called Kelvin waves. Rossby waves. Uh, there’s another tropical oceanic and atmosphere. A couple in called the Madden, Julian oscillation, or M J O. And the list goes on and on. And I have a casual understanding of a few of those, but the depth is really beyond me. I’m not going to go out on the limb and try to explain any of that. It’s not only would it turn this. Podcast into like a three hour podcast, but I’d probably have a lot of facts wrong. So I’m not going to do that. but I did want to call out that like everything in our sciences, we’re dealing with a very complex multi-variable system. So. We have to generalize a little bit.

[00:34:54] So forecasters are anticipating a strong El Niño this winter. And in case anyone’s listening to this in the distant future, we’re talking about the winter of 20 23, 20 24. So let’s look at why they’re saying that there might be a strong El Niño and what that means for our weather.

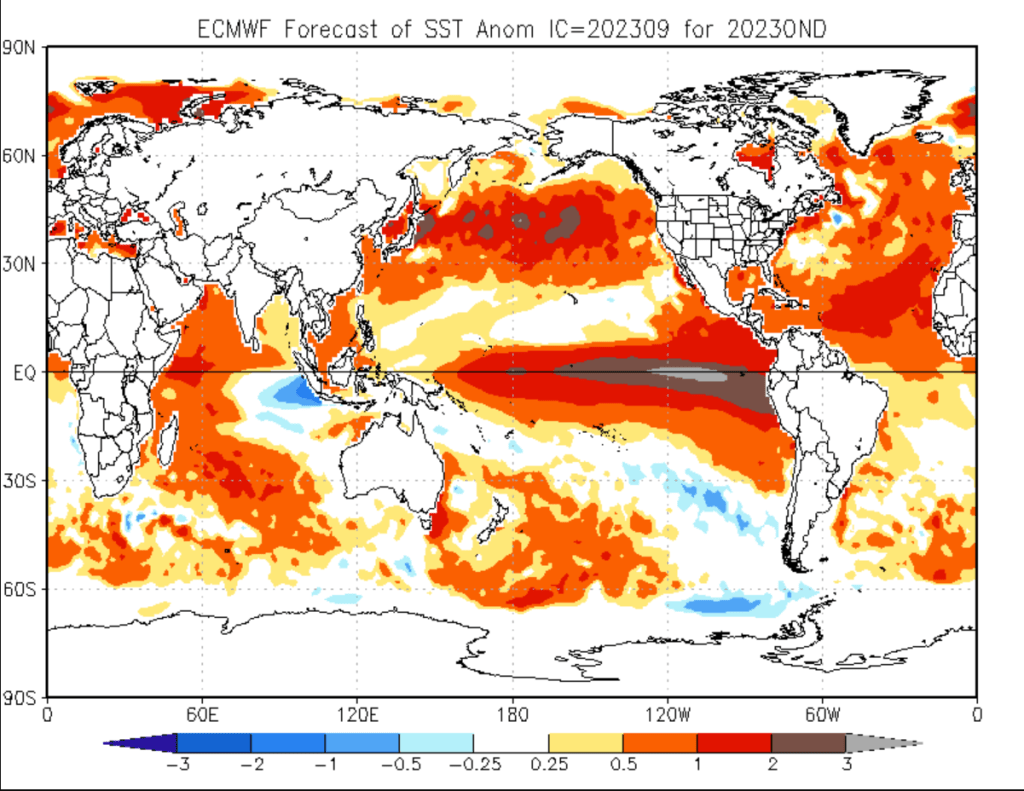

[00:35:12] In the United States, the national weather service, it’s part of the NOAA agency for national oceanic and atmospheric administration. Uh, the national weather service has a climate prediction center that focuses on things like this. And they’re the authority for ENSO predictions. They release a monthly ENSO report that anybody can download and look at and I’m going to link to it. Of course. Uh, this, uh, it’s usually around 30, 32 slides somewhere in that range and it includes maps and graphics and some interpretation of the current in the forecast and status. So in these reports, you’ll see that they look at sea surface temperatures across the whole range of the El Niño band. And they refer to these as like in so one through four. They keep track of the status and the trends and the models. They look at things like Kelvin waves and other factors that can contribute to El Niño. And from that, they develop a forecast.

[00:36:04] So the most recent update was on September 18th, just a couple of days ago. As I record this. And this forecast indicates a greater than 95% chance of El Niño through March of 2024. And the models also indicate a potentially strong El Niño

[00:36:20] but the strength of the El Niño is not the full story. Every El Niño is in fact different in its strength and its duration. You probably expected that that’s true for most weather. But additionally, the specific location. of these temperature anomalies in the ocean can also vary. And we talked about the coupling. So if the location of where the warm water pools, the most is different, you could expect a slightly different impact to the atmosphere. This year, we appear to have a more easterly event from what I’ve read. We’ll talk a little bit more about why that’s important here in just a moment.

[00:36:57] So let’s talk about. What might be the elephant in the room at least. Uh, I know for a lot of people, it is. And that is how is this thing that you’re talking about? That’s happening way down in the equator. Ocean temperatures in particular. Effecting weather way up here in north America and beyond in fact. And maybe you’re formulating some guesses, some hypotheses as to why that is. I gave a few hints already. So I’ll just tell you, there’s a lot of indirection here. It’s not like there’s a direct connection between what is happening. and the ocean waters off of Peru. And what is happening in New York?

[00:37:33] So simply stated. The changes associated with El Niño impact JetStream behavior. You’ve probably heard of a jet stream. It’s another one of those terms that your weather forecast or likes to talk about. There are typically several jet streams across the globe. Most often there are two in each hemisphere. There is a polar jet that runs closer to the poles and the subtropical jet that runs down kind of in the tropics. And these jet streams, they can move and wiggle that kind of move along with the tilt of the Earth’s , access season to season. And they can also have ripples and waves that bend. Uh, that could be bent by storms or high pressure systems. They’re called. , Ridges and troughs. And the jet stream. It’s also really important to storm tracks. It’s kind of like a path of least resistance. So El Niño. Can impact the subtropical jet stream pretty directly. what you see here is as warm water pools, you can create different systems, thunderstorm systems, things that, that make these little bulges and ripples, uh, along the subtropical jet. And this can have a broader impact on global atmospheric circulation, one jet stream changes and everything else changes a little bit as well. So bringing.

[00:38:47] The polar jet into the picture here. These changes in the subtropical jet stream can actually pull the polar jet further south. And that will bring storm tracks further south. Depending on where the ridges and troughs are. This can influence the storm track to bring more storms into California and across the Southern United States. And in turn, this leads to fewer storms in the Pacific Northwest in places like British Columbia during an El Niño year. So I have a link in the show notes that shows some maps of a typical jet stream set up for El Niño and LA Niña. I think this will really help with the visualization. You can see what the trends typically are.

[00:39:25] So with a further south storm track. You’re going over warmer waters with more moisture, you can , potentially pick up, uh, more. Precipitation in addition to just having more storms, hitting a certain location. So I keep using the word typical, and I want to remind everyone that there are all these other factors that I’ve mentioned. And even in a strong El Niño or a strong La Niña a year, the jet stream pattern is never rock solid. It’s not like it just stays stationary the whole winter. It will wiggle and move. and you can have some periods of wet or dry regardless.

[00:39:58] And this is where the nuance of statistics and probabilities really come into play. So I heard Daniel Swain of weather west. And by the way, if you don’t know Daniel Swain and you’re into this kind of stuff, you really should. he is a climatologist that has a great blog called weather west. He’s pretty prolific on Twitter as well, and has office hours on YouTube where pretty much every week he spends an hour kind of answering questions and describing things happening in the world. very well-spoken very knowledgeable meteorologist climatologist worth following. So his example here, talking about statistics and probabilities. Was like, imagine a situation where we say. Typically for this setup, we have a 50% chance of above normal precipitation over the winter. A 30% chance of average precipitation and a 20% chance of below normal precipitation. And to be clear, I just made those numbers up for the sake of example. That is not the exact probabilities that any one location has for the El Niño event this year.

[00:41:05] So you might hear that. And on the surface, it’s like 50% chance of above normal precipitation. Well, that’s like a coin flip. What value is there in this forecast? So, this is a bit of the nuance. When you compare a 50% chance of above normal precipitation to a 20% chance of below normal precipitation. You see, there’s a two and a half times more likely. Scenario that you’re going to have above normal precipitation. You can also slice it a little bit differently. Add up 50% chance of above normal, 30% chance of average. And you can say, well, we have an 80% chance. Of average to above average precipitation. Four times more likely than below average. So that gives you a good feel as to how to plan and how, how to expect. These are probabilistic predictions and they’re extrapolated across an entire season. Which will obviously have ups and downs. You might start off drier or wetter than expected, and then it changes for the rest of the season. For example.

[00:42:06] And the other big variable is exactly where the storm tracks are set up for the longest period of time. So some El Niños tend to focus a little bit further, south, such as Southern California for where a lot of storm systems will make landfall. And others may focus more in the central or Northern California. Time will tell it’s hard to say exactly. What’s going to happen here this year.

[00:42:30] One of the other unknowns. That’s. Kind of unique to this year and unique to some more recent years is that global oceans are warmer than normal. Kind of almost everywhere. And this is a hundred percent attributed to climate change and global warming. So the Northern Pacific is particularly warmer than normal. And again, this is not related to El Niño. This is just another factor. It’s not clear exactly how this will impact El Niño. Because again, there’s a couple of things. So this warmer north Pacific water. , combined with an El Niño has not been observed before. And this exact configuration. Maybe it will kind of offset the El Niño. But it’s also possible that this extra warmth. Over what would be the winter storm track? Could allow for more precipitation and stronger storms. It’s more energy. It’s more water vapor. And speaking of Daniel Swain. This is what he’s leaning towards at the moment based on his YouTube office hours that I alluded to before. So he’s suggesting that. They’ll probably be. A noticeable El Niño event that affects more southerly locations. Because of this Eastern, uh, location of the El Niño in general. And there may be some stronger storms , than usual because of this extra warmth in the Northern Pacific ocean. The other thing that he pointed out. Is that it often takes until late January, excuse me, late December or January for the effects of El Niño to fully kick in, in the Northern hemisphere. And I can remember the big El Niño and, uh, what was it? 1998. And that was definitely the case. Everyone was like, where is it? But when it kicked in at kicked in hard and it caused a lot of rain, a lot of landslides, a lot of flooding.

[00:44:10] Okay. Back to ecology for a moment. So if this El Niño impact pans out. As just described. It may mean the areas in Canada that have been ravaged by wildfire this year may actually see a dry winter. The storm tracks is going to get pushed further south. These wildfires have been occurring at a scale. That’s just really frankly, hard to imagine in the boreal forest up there. And some most are in very remote and very rugged areas. So believe it or not, there’s actually concerned. Some people think that some of these fires may actually persist over the winter. They may not be extinguished. And a bit of this is because even though it may get cold up there, they make it some snow, the really carbon rich peat areas. Which can accumulate very deeply. Um, in some of these systems, Can smolder and burn and actually underground retain their heat and smoldering. so without enough rain that will continue and they can re-emerge in the springtime or summertime. when the conditions are right, it’s pretty crazy to think about.

[00:45:13] And of course ocean temperatures are the primary habitat driver of the oceans themselves. So along the equator Marine life is going to dramatically change. As the water temperature has changed. In fact, one of the most famous early descriptions of El Niño comes from. At least as the legend says, Peruvian fishermen. They referred to the phenomenon is El Niño. Which in Spanish means the child or the boy. what they noticed was disrupted fishing patterns with the arrival of this warmer than normal water that often occurred right around Christmas time. Thus El Niño in reference to the birth of Christ.

[00:45:52] So here in north America. What can we expect? Well, I just mentioned. Southern California, maybe central California. Has a higher probability to not have seen more rain than usual this year at most storms may be. A little bit amped up from the warmer north Pacific waters. And this storm tract will typically also proceed along the Southern part of the United States like Texas and the Florida, which may see some wetter, snowy or cooler weather as a result. And then as you head north into the Northern Plains and the upper Midwest, it will probably be drier and perhaps even slightly warmer than normal. At least that’s what the typical trends show. Probabilistically

[00:46:33] And the areas that do see excessive rain, of course, this will lead to higher stream flows, possibly. Flooding in some spots.

[00:46:40] And these are important ecological processes. Even if they are destructive at times. Other areas might see warmer and drier conditions. Again, part of the ebbs and flows in. Whether that translate into some ecological winners and losers, at least in the short-term.

[00:46:56]

[00:46:56] Michael Hawk: Okay, so that about wraps it up. I hope you enjoyed the solo episode. I know that I enjoyed writing it. In fact, you know, let me know if he did enjoy it because I can consider doing some other topics in the future. I don’t have tons of these topics where I can just sit down and write out an outline for an episode and speak to it kind of freeform like this. But there are a few and yeah, maybe I can do more. And as I mentioned, I included a lot of great links in the show notes that include visuals of ocean currents, jet streams, Rossby waves and more. And I also linked to Daniel Swain’s website and his YouTube channel definitely worth looking at.

[00:47:31] I always learned so much from him.

[00:47:33] Thank you so much for sticking with me through this episode. I hope. Thank you so much for sticking with me through this episode. I truly hope you enjoyed it. And if you did.

[00:47:42] Please share it. It really means a lot to me. I appreciate all of you. Thank you.